What I’m about to write is actually really serious. But it starts with a lighthearted and completely true story.

Chainsaws for nature.

When I was in high school, instead of going to class on Thursday mornings, we students were required to do some kind of community service in the San Francisco area. One of my friends’ mothers had been involved in philanthropy with the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and had identified the perfect community service opportunity for a handful of mostly boys in our small group of friends: Cutting down a bunch of goddamn trees.

On our first day, we were driven out in a couple of Land Rovers to a meadow in the Presidio, somewhere southwest of the Golden Gate Bridge. There, we found ourselves in fields of tall grasses and weeds, a soaring landscape flanked by trees of various sizes.

We received some orientation. Some of the trees, we were told, were native to the region, and predated the European settlers of the 1700s. You could usually tell which those were by looking at the “under canopy.” If the ground beneath a tree was full of other greenery and various plant life, it was probably native. If the area was brown and barren, it was probably non-native, brought to the area more recently by the Spanish, most likely. It was pretty stark, and I was impressed.

Our mission was to help the men working out there prepare some of the non-native trees to be cut down. This would facilitate the land’s rejuvenation and restore its sustainability.

Using simple handsaws, we teenagers were to cut off as many of the smaller branches coming off of the main trunk of a non-native invasive species as we could. Once we’d cleared those away, one of the dudes with a chainsaw would come and fell that fucking tree. You know—for the environment.

“Are you guys, like, lumberjacks?” somebody asked.

“No,” a burly guy with a construction helmet and a gnarly chainsaw said. “We’re land conservationists!”

“This is weird,” I thought to myself, as I was handed a 22” Stanley Sharptooth and a ratty pair of gardening gloves. “But it’s kinda cool.”

So, every Thursday morning, we’d go over to the Presidio and get some of our pent-up teenage aggression out on those no-good non-native trees. From the standpoint of habitat restoration, we understood intellectually that what we were doing made total and complete sense. But, still, it felt like we were doing something vaguely wrong. Which is also part of what made it fun. We pretty much had one joke and it went like this:

“Hey Jesse!” I’d yell to my friend. “What are you doing?”

“Hacking trees!” he would reply, joyfully.

“Why!?” I’d yell back.

“To save the planet!”

This went on for some time.

A painful lesson: The Lāhainā, Maui fires.

Climate change is becoming increasingly dangerous not only because extreme weather events are seemingly becoming more frequent, but also because population growth and urbanization mean that when such events occur, they are more likely to happen in more densely populated areas.

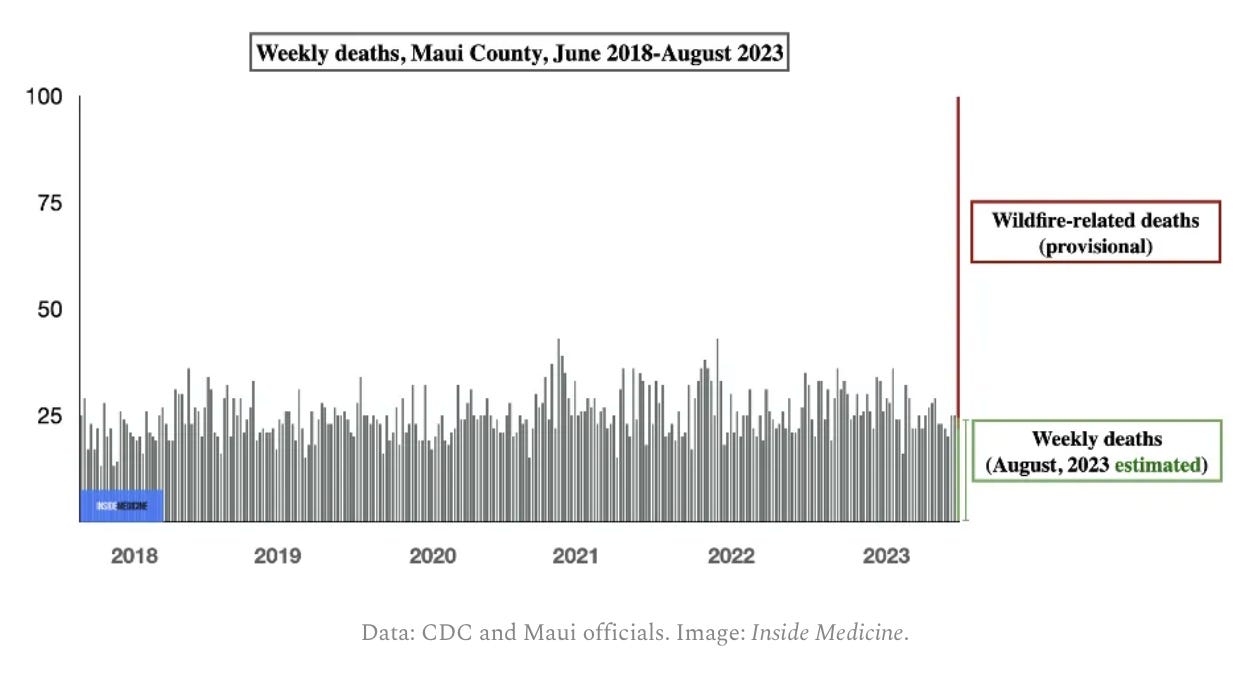

When the Lāhainā, Maui wildfire occurred in August 2023, I quickly realized that the approximately 100 resulting deaths had, in a sense, temporarily rendered climate change as the leading cause of death on the island. That, I believed, was unusual, if not unprecedented. I graphed that out using numbers in the media and wrote about that here in Inside Medicine.

Shortly after that, I was fortunate to be acquainted and connected with Dr. Kekoa Taparra, a Stanford physician-scientist and Native Hawaiian. Once I had official CDC numbers in hand, I could say that the Maui fires had almost certainly been the largest mass casualty event in its modern era. I graphed those data and shared them with Dr. Taparra because, quite frankly, I didn’t know what to do with that information.

Dr. Taparra had ideas though, and he brought in another expert, Mr. Kauanoe Batangan, of the County of Maui Office of Recovery to help. Kekoa and Kauanoe did the heavy lifting on drafting an essay discussing the implications of the Lāhainā fire, and what could be done to prevent such calamities in the future. I knew my expertise was limited to a couple of data contributions I could make and that I could help with a little bit of wordsmithing here and there. (You know I love to write, but in this “room,” I knew I was way out of my depth.) So, I did what I never do and took a back seat while Kekoa and Kauanoe dug in and wrote something truly original and important. I’m proud to share that our essay was published yesterday in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Below is the graph I contributed to the essay, using CDC data. In the essay, we mentioned an important fact about mortality data: there’s currently no classification for climate change, making it hard for epidemiologists to track the human toll of this human-made problem. As you can see, August of 2023 was just horrific. (You can also see that because Hawaii kept Covid-19 out until the vaccine era, the state did very well compared to others. At no point was Covid-19 the leading cause of death on Maui.)

More than words.

With each new draft of the essay that Kekoa and Kauanoe would share with me, I would have two reactions. First, I was grateful that they were using this essay as an opportunity to educate people (first me, then everyone else) about key concepts from Hawaiian culture, like:

Pilina—the importance of connections and trusted relationships in the community, essential for rebuilding.

Laulima—the “many hands” of cooperation/collaboration and community action.

Lōkahi—“unity” and harmony.

Second, I had to confront something uncomfortable—that the trappings of colonialism/modernity had probably played a major role in these deadly fires. Yes, modern Hawaii has many of the wonderful developments of the 21st century, like advanced medicine and technology that make life a lot more comfortable and livable. But the cause of this devastating fire has now been determined to have been a lethal combination of exposed power lines and the presence of kindling from non-native grasses. I think when people like me hear language that blames the Maui fires on colonialism, it’s understandable that we would want to reject such a notion out of hand as unfair or unsubstantiated. But, my friends, the scientific evidence is staring us in the face. In the last several decades, fires on Maui have most frequently occurred in areas dominated by non-native grass originally brought by Europeans, even though these species “only” cover around a quarter of Maui’s land.

When I read this in a report recently, I recalled the charming little tree-hacking anecdote from my high school days back in San Francisco. We’d all been amused by the surface-level cognitive dissonance—cutting down trees to make the world a better place. But the notion had genuinely been the right one. I now find that story a little less funny, and a lot more true. It’s even a bit profound. San Francisco conservationists were—and often are—ahead of their time.

The essay that Dr. Taparra and Mr. Batangan primarily wrote (and which I was honored to be a part of), lays out what must happen in the future quite explicitly. Some of what we say in the essay could quickly be shrugged off as idealistic, or a Romanticized nostalgia for a past that can’t realistically be restored. But that’s not correct. Nobody is imagining a world in which we can turn back the clock on the politics or on modernity itself. What is doable is to combine what modern ecologists and scientists have learned with the more sustainable and safe practices long implemented by Native Hawaiians. Nor does any of this negate the need for rational and scientific approaches to complicated problems. As I have observed it, many modern Native Hawaiians care deeply about their land not because they are spiritual. They are spiritual because they care deeply about their land. We would all do well to learn from that.

Recently Inside Medicine:

Questions? Comments? Join the discussion in the Comments section.

I am afraid this information about likely cause was well known to the utility before these events occurred, especially given the example of what had happened in California with PG&E.

A better question, and one that is much harder to answer, is why supposedly science loving blue states, states with a tendency towards regulation were so poor at preventative measures. In Hawaii's case in particular wildfire risk and poor forest management has been talked about for the past several years since the PG&E fires happened. I guess people only learn by having it happen to them.

It's still pretty hard to "improve" upon "nature". Just shows what billions of years of the trial and error of evolution has accomplished.