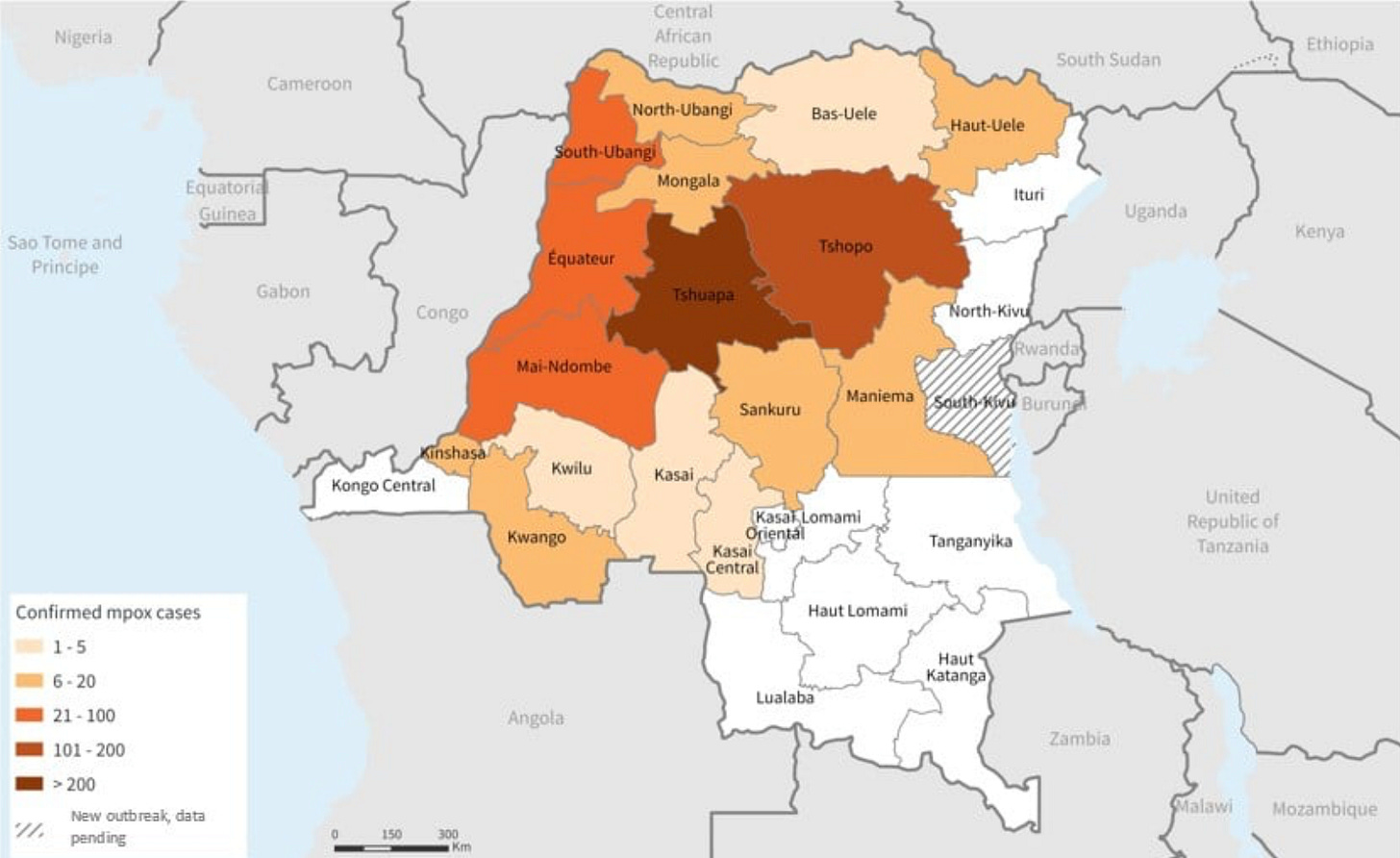

An outbreak* of Mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) has been detected in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The WHO has reported that the case fatality rate—the percent of detected cases that are fatal—is 4.6%, or 1 in 22. That represents 581 deaths among 12,569 suspected cases in the 2023 outbreak. This is high. By comparison, the Mpox outbreak of 2022 that was declared a “public health emergency of international concern” by the WHO had a case fatality rate of 0.18%, or 1 in 500. In the DRC, the case fatality rate of the 2022 outbreak was similar to the global rate, at around 0.2%. (The official international emergency that started in July of 2022 ended in May of 2023. While technically the current cases are an “escalation” of a longstanding Mpox outbreak in the DRC, for the sake of clarity, I’ll use the terminology of the 2022/clade II and 2023/clade I outbreaks here.)

The fatality rate of this new escalated outbreak that took off in 2023 is startling.

But what does it mean? Let’s talk through this.

What might explain the higher detected fatality rate in the new Mpox outbreak?

There are three major possibilities that might explain why the Mpox outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has a 25-fold higher case fatality rate so far.

Something about the strain virulence.

Something about testing.

Something about the population affected.

Let’s start with the strain. The current outbreak in the DRC appears to be due to a different strain of Mpox (“clade I”) compared to the outbreak that began in 2022 (“clade II”). In the past, clade I has been considered deadlier, but it’s unclear if that is related to the virus itself, or the risks and medical resources of the people it infected. I couldn't find any head-to-head comparisons. But to be “safe,” we’ll assume that clade I is indeed deadlier than clade II. (You’ll see below why this might not be the major driver behind a 25-fold increase in lethality.)

Next, let’s talk about testing. Case fatality rates are highly dependent on testing strategies. Let’s use Covid-19 as an example. If you tested 100 vaccinated and otherwise healthy college students, the case fatality rate might be 0%. If you tested 100 unvaccinated seniors in an ICU, it might be 15%. In the case of Mpox testing in the DRC, there’s little reason to think that the age is different in this new outbreak. But given that officials would have initially been “caught off guard,” it’s extremely likely that milder cases are going untested (and therefore undetected) during the current outbreak.

Why do I think this is what is happening? “Test positivity.” Test positivity is the number of cases detected/number of tests administered. High test positivity can mean two things: 1. Increased disease prevalence; 2. Under testing (mild cases are not being detected). The second option is most likely. How do we know? Because the test positivity in the DRC during this new outbreak has been reported as 65%. That means for every three tests done, two are positive. That’s way too high to reflect the true prevalence of the disease in the population; there is no way that two-thirds of the country has had Mpox during this outbreak. Meanwhile, in 2022, the test positivity rate in the DRC was 27%—lower than 65%, but still incredibly high. (We had far lower positivity in the US.) It’s likely that the real prevalence was several orders of magnitude lower than 27%.

Finally, let’s look at the population affected. The thing to know is that Mpox fatalities hinge almost entirely on immunocompromised status. In the 2022 outbreak, around 40% of Mpox cases occurred in people with HIV. That’s not a biological thing, by the way. That’s a behavioral thing. Anyone can get Mpox. But outcomes are another story. Outcomes heavily depend on immune status. Virtually all Mpox deaths occurred in a subset of HIV-positive people with very low T cell counts (that is, T cell counts low enough to imply long-standing untreated HIV, which comes with high risks of otherwise rare infections; this is what is called AIDS, as opposed to HIV, which is the infection itself). In a major study, HIV-positive people with T cell counts <100 had an Mpox case fatality rate of 27% in 2022. By comparison, HIV-positive people with T cell counts >200 had a 0% case fatality rate. (T cells counts in both HIV-positive people who are being treated and HIV-negative people tend to range from 400-1,600.)

Running some numbers.

Can changes in just three parameters—the strain, the affected population, and testing strategy—explain a 25-fold difference in the case fatality rate during the 2022 and 2023 Mpox outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo? Yes, they certainly can. Let’s apply a few numbers and see what happens.

For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume clade I (2023) is genuinely twice as deadly as clade II (2022) among people with advanced AIDS (HIV-positive with T cell counts low enough to qualify as severe AIDS). That would mean an Mpox case fatality rate of 50% for people with AIDS in the 2023 outbreak, compared to 25% in 2022. Next, let’s assume that the difference in test positivity between 2022 and 2023 reflects less testing rather than prevalence (reasonable, because both numbers are way to high to be realistic reflections of prevalence). That means that in the current outbreak, officials are missing around 60% of the cases in late 2023 compared to what would have been detected with the same amount of testing as the 2022 outbreak. So, instead of ~12,500 cases suspected so far, the number would be closer to 30,200 in apples-to-apples testing regimes.

Given those two assumptions, how much more of the affected population would have to have advanced AIDS (i.e., HIV with T cell counts <100) to explain the rest of the difference in the 2022 and 2023 outbreaks?

Assuming (as above) that decreased testing means there “should be” 30,200 cases out there, we can work backwards. Let’s again assume the clade I (2023) is twice as deadly to people with AIDS as clade II was (2022 and, as before, virtually all deaths occurred in people living with advanced AIDS). If, as before, 40% of people infected with Mpox were also HIV positive, the share of HIV-positive people with advanced AIDS would need to rise from around 2.2% to 9.6%. Given the report from the WHO, this would be very credibly explained by slight shifts in epidemiology of the current outbreak. Per reports, the 2023 clade I outbreak has been spreading among sex workers and in sex clubs (of which there are around 50 in the DRC, a nation of 110 million people) patronized primarily by men who have sex with men and who, unsurprisingly, have many partners in a short period. While some of the same establishments may have been involved in the 2022 clade II outbreak, it wouldn't take much more than a few changes in these variables to explain all of this. Which exact clubs were affected? Who happens to be attend those certain clubs? Such changes could easily change the risk pool enough to have answered our question.

One semantic thing.

The WHO reports that the DRC outbreak of clade I of Mpox is the first in which sexual transmission of this virus has been described. I continue to believe that this is a mislabelling. Yes, sexual contact is one possible way to acquire Mpox. But basically from what I can determine, a person can get the virus from close (and “prolonged”) contact with a lesion anywhere on the body. So, whether a person touches a lesion on the trunk or the genitals, the issue is the contact—not the location of the contact per se. In contrast, HIV is only contagious from one person to another through sexual transmission. That is, any other form of touching (including sharing saliva), will not spread HIV. So, while sex is a “great way” for someone to become infected with Mpox, I’m a little mystified that the WHO is claiming sexual transmission—which again is different from touching a lesion that happens to be in the genital region. If there are ironclad data to support sexual transmission (as opposed to lesion contact wherever that lesion may be), I certainly have not seen that.

Why do I care? Because I don’t want people misled in either direction. On one hand, nobody is going to get this virus from casual (read: brief and/or incidental) contact. In that light, please don’t worry. Cases of spread from non-intimate touching are so rare that they literally warrant case reports in the medical literature. On the other, I don’t want people engaging in potentially high-risk behavior to think they can’t get Mpox from intimate contact that is not actual sex. That’s wrong, and it would be false reassurance to say otherwise.

Should we be worried?

When I think about Mpox, I worry about high-risk people. In the US, for example, the 2022 outbreak caused 38 deaths (out of 30,235 cases by the time for a case fatality rate of 0.13%, or 1 in nearly 800 cases). Of the 33 deaths we have information on, 31 were among people with advanced AIDS; the other two were in people with profound immunocompromise for other reasons (one being an organ transplant recipient on immune-suppressing medications). In particular, I worry about people who are not receiving antiviral treatments for HIV who need to be. I also worry about equity in who may receive hard-to-get medications among infected people, as well as vaccine access for high-risk groups. So, I’m not worried about most people. I’m a little worried about healthy people with high-risk behaviors—but even most of that population will "be fine.” (People with properly-treated HIV are not high-risk, an amazing sign of how far we’ve come with that disease.)

What concerns me are people with a combination of behavioral risks, extremely vulnerable immune systems, and lack of access to medications that both prevent and treat Mpox. I also worry that until people in the West start getting infected again, the right resources won’t be mobilized.

*While technically not a new outbreak, but an ongoing escalation of an existing one, it’s a big enough change that the term makes sense to use here.

Questions? Comments? Join the conversation below…

Another interpretation to explain high positivity rates is that physicians diagnostic skill increases. They test fewer patients whom they believe have a low probability of having disease. This may be particularly true in a resource poor area either because patients can’t afford the test or it isn’t easily available.

Very good data & citations Dr. Faust, as usual. ✍️ Thx.