The Omicron Paradox: If it’s milder, why are hospitals on the brink of disaster?

Hospitals started this wave fuller that previous ones and Omicron isn’t nearly mild enough.

Based on emerging data from South Africa and now the United States, it appears the rate of people infected with the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 who require hospitalization is genuinely lower than what was recorded during prior waves. Does that mean the Omicron variant really causes milder Covid-19 illnesses than its predecessors, as has been widely speculated? Or are vaccines and prior infections just providing more protection?

To find out, I asked researchers in South Africa for data from their recent Omicron wave. I wondered how frequent Covid-19 hospitalizations were during their recent Omicron wave compared to the prior Delta wave. They told me that after taking vaccination and immune status, age, and medical co-morbidities into account, the risk of Covid-19 hospitalization was around 50% lower during the Omicron wave compared to the Delta wave. That means Omicron hospitalized its targets less often than other variants had both as a result of its biologic characteristics and community immunity from vaccines and, likely to a lesser extent, prior infections.

If this sounds like good news, that’s because, in isolation, it is. Imagine if Omicron caused severe Covid-19 just as often as Delta and other previous variants while spreading as quickly as Omicron does; more hospitals would have overflowed sooner and by greater margins than what appears to be happening now.

However, any discussion of Omicron’s lower rates of hospitalization that is devoid of the context of its cinematic contagiousness misses a devastating and important point. Whether due to our behavior or its biology, Omicron is spreading through cities, counties, and states like fire in wind. Hospital beds are filling up fast because Omicron’s rate of spread appears to have quickly overtaken any felt benefit resulting from a lower rate of hospitalization.

The visualization below created for Inside Medicine by Dr. Kristin Panthagani demonstrates this concept dramatically. Using realistic estimates of emerging data, we show how a variant spreading as quickly as Omicron (“Virus O”, right) would be expected to fill up hospital beds faster than a variant like Delta (“Virus D”, left)—even if Omicron “merely” hospitalizes half as many of its new targets as Delta did.

As the visualization shows, even after a few "cycles," a less virulent pathogen like Omicron will cause far more hospitalizations (red) than one like Delta, largely because of how many more infections it causes (gray).

•••

Another important problem is that, unlike previous waves, United States hospitals entered the Omicron wave already facing pressure from high demand for non-Covid-19 care. In addition to other “typical” problems that seem to mount in winter, flu is back after a hiatus last year. Entering the Delta wave, on July 1st, 2021, around 67% of staffed hospital beds in the United States were full. Leading up to the Omicron wave, around 79% of staffed beds in the US were full. That 12% is important buffer territory that we desperately need. Things get dicey in hospitals the closer to full we get.

•••

But what about younger demographics getting Omicron? Does this not help in some way? Yes and no. On one hand, younger populations getting most of the Omicron infections means that hospitalization rates are likely to be lower. Indeed, that’s what we’ve seen so far. But that’s a double-edged sword. Younger people also staff hospitals. Right now, so many healthcare workers are being sidelined with Omicron that our ability to care for all patients, Covid and non-Covid alike, has been noticeably compromised in many places.

On top of that, the rate of Omicron spread is outpacing any benefit hospitals might have felt owing to lower rates of hospitalization. The graph below (made by Benjy Renton and me), shows how in Florida for example, the number of new cases needed for hospitals to exceed capacity has actually increased in the last couple of weeks (we call this number a “circuit breaker threshold”). If the hospitalization rate among Omicron cases is lower—which indeed we’ve seen in many places including Florida, where the rate of hospitalization among new SARS-CoV-2 cases has dropped by more than 50% since mid-December—a region should be able to “tolerate” more new cases before hospitals will fill up. (Note: some, though not all, of this lower rate of hospitalization reflects increases in testing among younger healthier people). Unfortunately, the graph also shows that Omicron’s rapid spread has already overcome that increasingly higher "circuit breaker" capacity threshold. In essence, Omicron’s lower hospitalization rate meant we had more money in the bank to spend. But we’ve already spent it all. In fact, whenever the yellow line is on or above the blue line, we've gone into debt.

•••

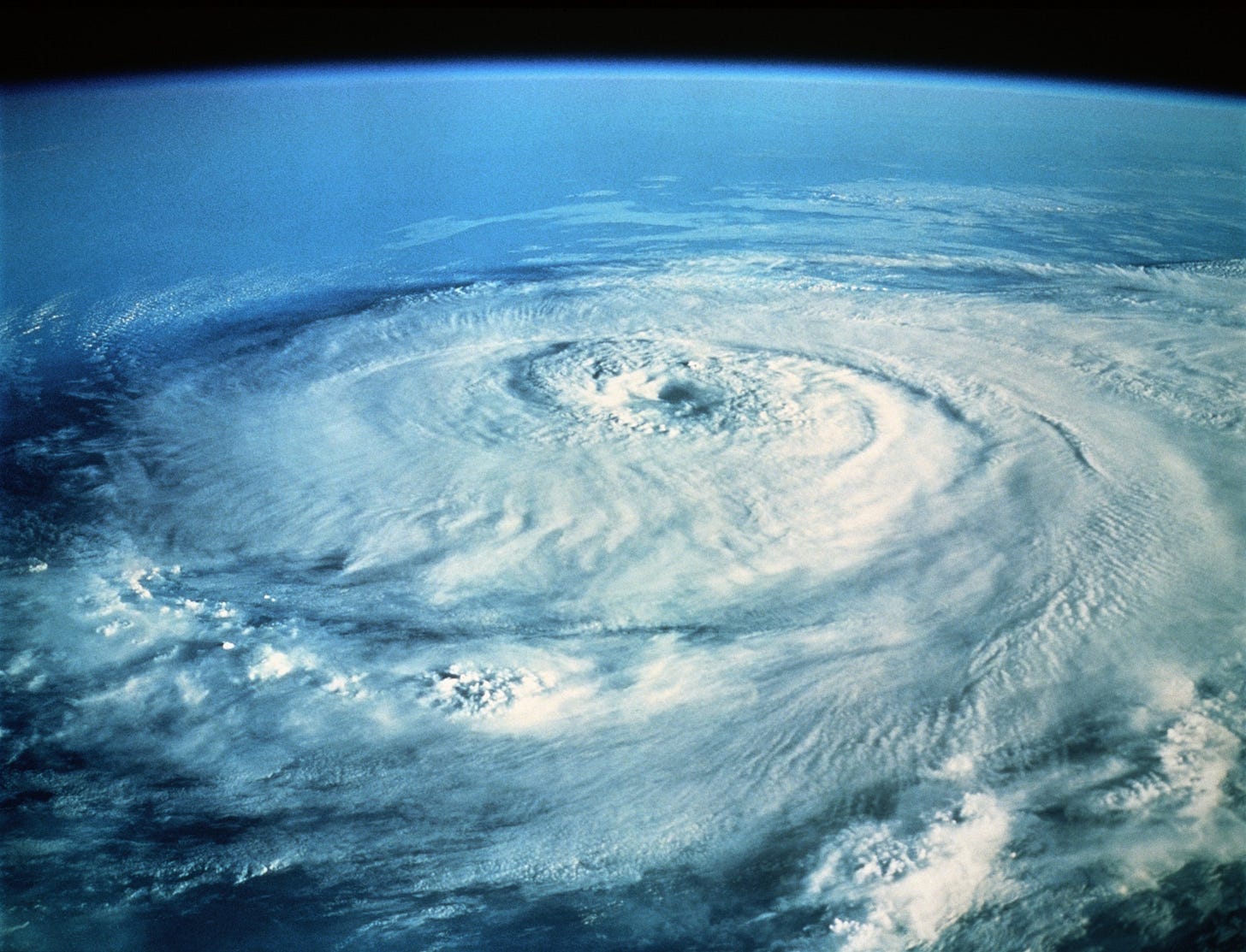

My friend Dr. Carter Mecher, who served as Director of Medical Preparedness Policy at the White House under both President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama, shared a great analogy with me over the weekend. “If Delta was a Category 5 hurricane, Omicron is a Category 2 that moves ashore and just sits there until everything is flooded and just about everything is damaged,” he wrote to me in an email. “Hurricane Omicron doesn’t have the windspeed to rip off the roofs and flatten buildings. It just damages the roofs enough and floods them with massive rainfall, destroying the building just the same.”

Just a little bit more water in a building that’s already water damaged is enough to cause irreparable damage. That's how life in many US hospitals feels right now. The looming question is, just where are we in this storm?

•••

❓💡🗣️ What are your questions? Comments? Join the conversation below!

Follow me on Twitter, Instagram, and on Facebook and help me share accurate frontline medical information!

📬 Subscribe to Inside Medicine here and get updates from the frontline at least twice per week.

Special thanks to Dr. Glenda Gray and Shirley Collie for providing unpublished data from South Africa described here, and to Benjy Renton for data acquisition.