Spinal cord stimulators fail to show benefit in a bold new clinical trial.

I’m an ER doctor and a researcher and Inside Medicine comes out at least 5 days a week. How is that possible? With the generous support of readers (a.k.a, “the Insiders”). That partnership will keep this newsletter coming out every day, free to everyone, from public health officials, to you and your family. To help make Inside Medicine sustainable…

A striking new study conducted in Norway, and published in the Journal of the American Medical Association last month found that spinal cord stimulators for low back pain and sciatica—that is, pain radiating down the legs because the spinal cord is being pinched, usually by a slipped disc—did not help patients. I’ll describe what made this study so bold and what researchers found. But first…

A little background. I’ve got skin in the game here. I’ve had low and middle back pain since my 20s. It has always been mild, so I’ve been able to manage things with anti-inflammatory medications, and, in the past, occasional local anesthetic or steroid injections. The biggest determinant of my level of pain, I’ve found, is ergonomics. That comes down to three things: my weight, my posture, and the mattress I’m sleeping on. Weight loss helped a lot (I’m around 20-25 pounds lighter than I was during parts of medical school). Not being forced to stand for hours on end has helped (again this was wrapped up in my medical training; the operating room during medical school and prolonged rounding when I was a resident working in the hospital wards did not help my back one bit). And, recently, a new mattress has helped. (If I’d known what a difference that would make, I would’ve gotten this new one much sooner!)

So, as a person with early onset but well-controlled back pain, I keep my eye on various treatment options that I may eventually need to consider. Surgery and spinal stimulator devices, two invasive options, hold both the most promise and the most risk. Going to the operating room and possibly having a medical device placed into the spine are not options to be taken lightly. If they work, then great. But each comes with the risk of potentially debilitating complications.

Where do things stand on treating lower back pain/sciatica?

Epidural steroid injections:

The data are not encouraging. It seems like the benefits are modest, and often all-too-brief.

Spinal surgery:

Things may be improving here. Some earlier well-performed studies comparing surgery to conservative treatments were disappointing, showing some improvement for a few months, but not over 1-2 years. But newer techniques seem to hold some promise.

Spinal Cord Stimulators and the latest data:

Spinal cord stimulators have become increasingly used for patients with low back pain that has not responded to other treatments. The idea is appealing: surgically implanted devices deliver high frequency electrical bursts into the spinal cord, modulating pain signals before they reach the brain.

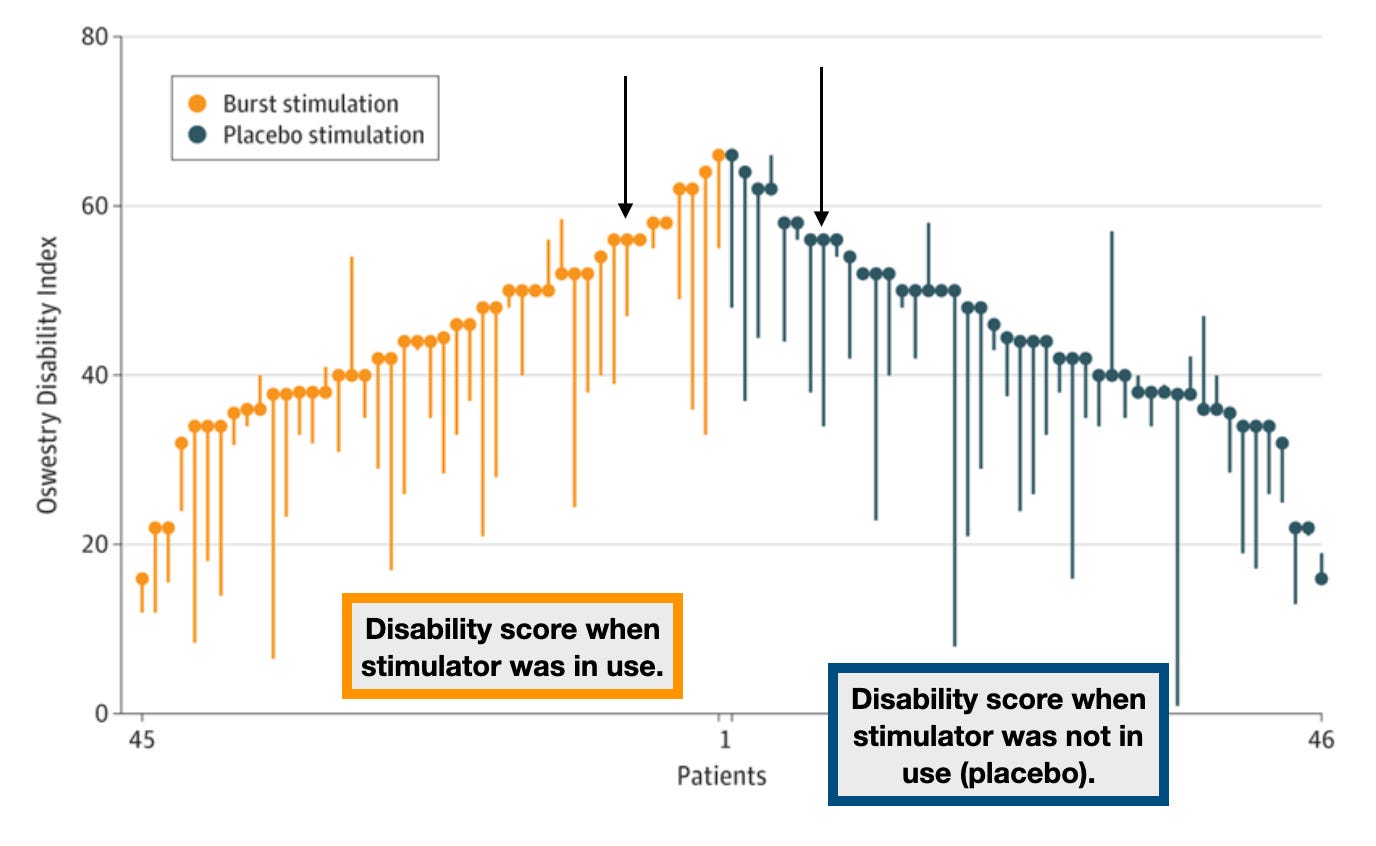

Some studies showed promise, but they were hopelessly confounded by a lack of blinding. That’s why this new JAMA paper is so interesting (and, spoiler, disappointing). Surgeons implanted stimulators into all of the patients who met their study criteria, a group of people with fairly debilitating pain who had already undergone surgery with inadequate improvement. The doctors made sure the devices worked by delivering electric bursts that the patients could feel—masking pain with a tingling sensation. Only patients who reported improved symptoms during this lead-in period were kept in the study. The researchers then did what’s called a randomized crossover. For a month at a time, the patients either received electrical bursts (which they could no longer feel; the settings were changed to eliminate the tingling feeling, but the hopefully helpful electric bursts were still being delivered) or nothing happened when the device was activated (i.e., placebo). Patients never knew whether their device was on for that month or not. Each month, patients reported their symptom scores (using a vetted metric called the “Oswestry Disability Index”). At the end of the study, there was no clinical (or statistical) difference between when the devices were delivering bursts of electricity to the spine versus when they were not. On average, disability scores went down a little bit in each group. In short, the effects basically boiled down to a placebo effect.

Okay, but if placebo works, why not place the devices on those grounds alone? First, placebo effects fade—and they’re probably unethical, outside of clinical trials. Second, the complications related to the placement of these devices should not be ignored. 18% of patients in the study had an adverse event, ranging from the accidental cutting of some fibers in the spinal column to infection to trouble urinating. Some of this might be tolerable, if the devices were helping enough patients. But that’s not what researchers found. I have seen complications from these devices. When things go awry, it isn’t pleasant.

Bottom line:

Spinal cord simulators did not help patients with lower back pain/sciatica that had also failed other treatment approaches. I hope the results of this study are appreciated by experts in the field in two ways. First, the results indicate that device developers need to go back to the drawing board. This technology seems to have failed. Perhaps another one (or improvements to this one) will succeed. Second, until there’s evidence that these devices work, they should be offered to patients far less often, if ever.

Did you find this helpful? Inside Medicine is written five days per week by Dr. Jeremy Faust, MD, MS, a practicing emergency physician, a public health researcher, and a writer. He blends his frontline clinical experience with original and incisive analyses of emerging data—and to help people make sense of complicated and important issues.

Did you like this? Please share it and follow me on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook!