Paxlovid or your statin?

Patients on some medications are sometimes told they can't take Paxlovid. Is that the right move?

Scenario: You’re diagnosed with Covid-19. You’ve been taking a statin to lower your cholesterol for years. But you’re told that the statin has a potential interaction with Paxlovid, the blockbuster Covid antiviral that decreases hospitalizations and death. Should you temporarily stop taking that statin and take Paxlovid for 5 days to decrease your chances of a bad outcome due to Covid?

This question comes up a lot.

First, if you take any statin other than lovastatin, simvastatin, atorvastatin or rosuvastatin, the answer is easy. If you have high-risk conditions for Covid, you can add Paxlovid on top of those other statins without concern for any unsafe interactions.

But what if you take lovastatin (Altoprev), simvastatin (Zocor), atorvastatin (Lipitor) or rosuvastatin (Crestor)? Pfizer says that its drug Paxlovid can have drug-drug interactions with these medications, and that the combination could lead to unsafe muscle breakdown. That in turn could lead to kidney problems or even death (albeit that is exceedingly rare). Accordingly, the FDA advises patients to stop taking their lovastatin or simvastatin 12 hours before the first dose of Paxlovid, and to resume the statin 5 days after they’ve completed the 5-day antiviral course. For atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, the contraindication is less strong and the FDA says that clinicians should “consider” temporary discontinuation of these drugs, but only during the 5 days when Paxlovid is being taken.

However, it seems that a group of patients are not being prescribed Paxlovid because they take a statin. On Threads, 24% of respondents to an informal poll I posted said that they’d been told not to take Paxlovid because of a drug they take. Of those, 76% said the drug was either a statin, blood pressure medication, or a blood thinner. (On Twitter, I posted the same poll and it yielded similar results.)

Rather than telling their patients to hold their statin, blood pressure medication, or blood thinners for a week, many doctors are just not prescribing Paxlovid to patients on these medications. Yes, these drugs decrease the long-term risk of heart attacks or strokes. But by how much in a 5-10 day period? Enough to offset the benefits of Paxlovid in very high-risk populations?

Has anyone done a risk-benefit analysis on this?

If it is out there, I have not seen it.

So, fine, let’s do one ourselves!

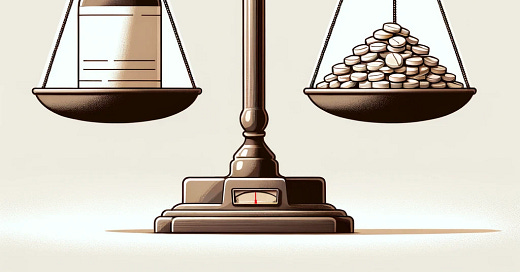

Let’s look at the choice between continuing to take a statin and Paxlovid. The decision really boils down to one question: Which is the greater, the decrease in Covid-19 mortality due to Paxlovid, or the increase in cardiovascular disease death resulting from skipping 5-10 days of a statin? Put another way, if Paxlovid decreases the percentage of people who die of Covid more than the statins decrease the percent of people who would die from a heart attack in the period they stopped taking them, the correct strategy would be to take Paxlovid and temporarily hold the statin.

We basically know the answer to these questions, though with Paxlovid, the benefit has changed (i.e., decreased) over time as the population has gained immunity to Covid.

What is the worst-case scenario for temporarily not taking a statin for 10 days? Let’s look at the group with the very highest cardiovascular risks—because if the analysis favors temporarily stopping their statin in favor of Paxlovid, so can everyone else. Research of people ages 65 and up who survived a recent major heart attack tells us that the 1-year mortality rate following the event is around 24%. While most of that 24% died within 6 months of the event (making the second 6 months much lower risk), we can conservatively assume that the post-heart attack mortality rate for the first year is around 0.66% every 10 days. Let’s just assume that all of the patients in these heart attack follow up studies were taking statins (most were), and that statins reduce the risk of another fatal heart attack by 25%. If we assume that stopping the statin immediately erases the entire benefit of taking the drug (which is not remotely true, but I’ll go with this just to be extremely careful in our analysis), the 10-day mortality rate would rise to 0.82%—that is, an increase of 0.16%.

Does Paxlovid decrease the risk of death in these patients by more than that? In the pre-vaccine era, the answer was not even close: yes, yes, a thousand times yes. The absolute reduction was more like 1% (and the relative reduction more likely 85%-100%). But today, an era in which everyone has been vaccinated, infected, or both, Paxlovid’s absolute benefit is far smaller. Yes, it still works for high-risk people, but the absolute effect has gone down dramatically. The first major study looking at Paxlovid during the vaccine era found that among people ages 65 and up, Paxlovid use was associated with a decrease in mortality from 0.39% to 0.08%—a decrease of 0.31%.

That means that even for extremely high-risk cardiovascular patients ages 65 and up—people who had recovered from a heart attack within the last year—the mortality increases of stopping a statin for 10 days might at most be around half of the mortality decrease associated with Paxlovid. And that’s if holding the statin for 10 days completely eliminates the patient’s lowered heart attack risk by virtue of their statin use. And for people more than a year out from their heart attacks? The hypothetical worst-case scenario mortality risk increase of holding that statin for 10 days would be just 0.07%.

Raw terms: The above numbers imply that for the population aged 65 and up we’re considering, around 1 in 608 people who survived a heart attack within the last year might die due to another heart attack during the 10 days of skipped statin doses, assuming the statin’s effect is all we’re giving it credit for (and, again, likely it’s a much smaller effect). For people more than a year out from their heart attack, holding the statin for a week might come with an increased mortality risk of around 1 in 1,460 people. Meanwhile, Paxlovid’s effect in similar patients would be associated with a decrease in mortality for around 1 in every 322 people who took it during the vaccine era.

Now if, you’re over age 65 and less than 6 months out from a heart attack (or recently had a coronary artery stent placed for very bad angina), skipping the statin might not be the right move. It depends on the situation, and also, just how much those missed statin doses actually matter (i.e., less than we said). Despite our conservative assumptions in the math above, the accrued benefit from taking a statin for months or years does not immediately fall to zero by skipping it for 5-10 days. Cholesterol levels take time to build up and to confer risk. What’s more certain is that as we progress from 6 months to a year out from a heart attack, the scale would seem to tip heavily in favor of Paxlovid, rather than staying on the statin instead.

What about people who have not had a heart attack but are at risk of one? Their risk of skipping the statin is far, far lower. The analysis would so heavily favor Paxlovid that the math is not even worth doing.

Unfortunately, at least some doctors are getting this wrong on the ground. Of the few (but mighty) people who reached the third question in my Threads and Twitter polls (which asked “If the relevant drug [which prevented you from getting Paxlovid] was for anything cardiovascular, have you ever had a stroke or heart attack?), most said “No, but I am at risk.”

Le sigh! By far, the highest risk cardiovascular group are those who have already had a major heart attack. A bunch of patients who have far lower mortality risks than the ones we just decided can skip their statin for 10 days are apparently being told by their doctors that it’s too risky for them to skip their statin in favor of Paxlovid. Unless Paxlovid really does not work in vaccinated people at all (and we’ll finally get randomized clinical trial data on this later this year, I am led to believe), this is pretty bad decision science.

Now what about people under age 65? I have not done the analysis. The risk-benefit balance would hinge on how much Paxlovid helps younger people with high-risk conditions for Covid-19 and what their post-heart attack mortality risks are at any given time. The answer is not straightforward because on one hand, the benefit of Paxlovid is substantially smaller than older people with those same conditions (in fact, in that big study I mentioned above, the associated benefit for Paxlovid use among at-risk patients ages 40-64 was actually nil). On the other hand, the one-year mortality among heart attack survivors under age 65 may also be a lot lower. There are too many variables for me to plant a flag on this one.

Other meds. Lastly, there are many other medications that have possible interactions with Paxlovid. Some are related to heart disease, including blood thinners and blood pressure medications. For these, it also seems highly unlikely that skipping them for 5-10 days would be as dangerous as passing on Paxlovid among the truly high-risk population that benefits from it. The same analysis as above would also apply to those medications; the upshot is that the short-term risk of a fatal heart attack is just not that high, even among fairly recent heart attack survivors (that is, more than a few months out). Some drugs on the Paxlovid interaction radar include certain types of chemotherapy and drugs that prevent seizures. The list is not short and in some instances, the correct choice is not immediately obvious.

Decision science is not easy.

Each decision, made properly, should reflect a careful comparison of the risks of temporarily stopping one medication against the opportunity costs of foregoing Paxlovid. To make the right call, doctors have to know how much the risk increases on one side of the ledger, and how much Paxlovid decreases risk for the patient in front of them, on the other.

How many doctors have the time—let alone up-to-date information to draw on—to get these decisions right? Very few. It’s not their fault. There are simply too many variables to keep up with. Down the road, this will be a perfect application for AI. At the moment, though, there’s no reliable tool for these assessments. Your doctor may not have exact numbers to cite when you ask about this. But it’s still good to ask if you have concerns. Sometimes a good question is enough to get us thinking…

Do you have any sense of what would happen to you if you didn’t take your medications for a few days? Obviously it depends on the condition, but I wonder how well patients understand their short-term versus long-term risks related to their various medications. I’d be interested to know if you have a sense of these things and I’m eager to hear your thoughts. As always, I’ll be happy to engage in the Comments section!

Dr. Jeremy, once again I'm wowed by your dedication to public health issues and particularly COVID while so many hide their heads in the sand. I have avoided COVID so far mostly due to vaccines and living a very isolated life as I'm highly immune compromised due to Progressive MS breathing issues, being in a wheelchair, "big gun" drugs for the MS that knock my B and T cells to zip and also having Common Variable Immune Deficiency, and heart/stroke issues related to MS. And this month I was diagnosed with breast cancer, again. I'm also on a satin drug and this is good practical info for people like myself. (How do you possibly find time for this? Hoping you relaxed a bit on vacation.) And since Med page just put out an article that people like myself with neurological issues being more susceptible to Long Covid issues. What we do to protect ourselves can so often help others more vulnerable. Then we can participate more in helping others. Prime example, the MA Wheelchair Repair Bill passed the state Senate yesterday largely because disabled chronically ill patients pushed themselves further to advocate for themselves and others. We worked on it right through the holidays, non-stop. We're all stronger together. Thank you for all your advocacy and research. It really does count. Happy New Year.

Very interesting article. I faced this dilemma when I had COVID in October. In the end, I did opt for stopping the Statin and taking Paxlovid. I didn't want a repeat event of the virus I had in Jan-Feb 2019. Which caused a Pericardial Effusion. The provider concurred with my thinking at the time that stopping the statin for a few days would not increase the risk too much.