Obesity rates finally went down in the US. Could Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro feasibly be the reason? Yes.

Recently, the Financial Times data reporter John Burn-Murdoch published an amazing graph showing that, apparently for the first time in decades, obesity rates in the United States had gone down. Burn-Murdoch wondered aloud whether GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro might be responsible.

Having thought about this carefully, I actually do think it’s possible, despite what some other analyses have concluded. But Burn-Murdoch’s article vexed some experts in public health for several reasons:

The CDC data on which it was based did not find a statistically significant decrease in obesity, only a numerical decrease.

Some claimed it is just too soon for GLP-1 drugs to have made a measurable difference at the population level.

If obesity has gone down, why has the rate of mild-to-moderate obesity gone down, while there has been an increase in severe obesity rates?

Correlation is not causation; the data are not proof that the GLP-1 drugs are responsible for the change.

The only one of these arguments that I’m convinced is correct is the last one. The rest are actually limited interpretations based on insufficient analysis, and if you stick with me, you’ll soon learn why, and why I do think these data may be meaningful and that the GLP-1 drugs may be involved.

Certainly this all piqued my interest. Mainly, I wanted to know whether it is even possible for GLP-1 drugs to have already lowered the national rate of obesity in the United States.

To get at that, we need to address the issues above, one by one.

1. What the new obesity data actually say.

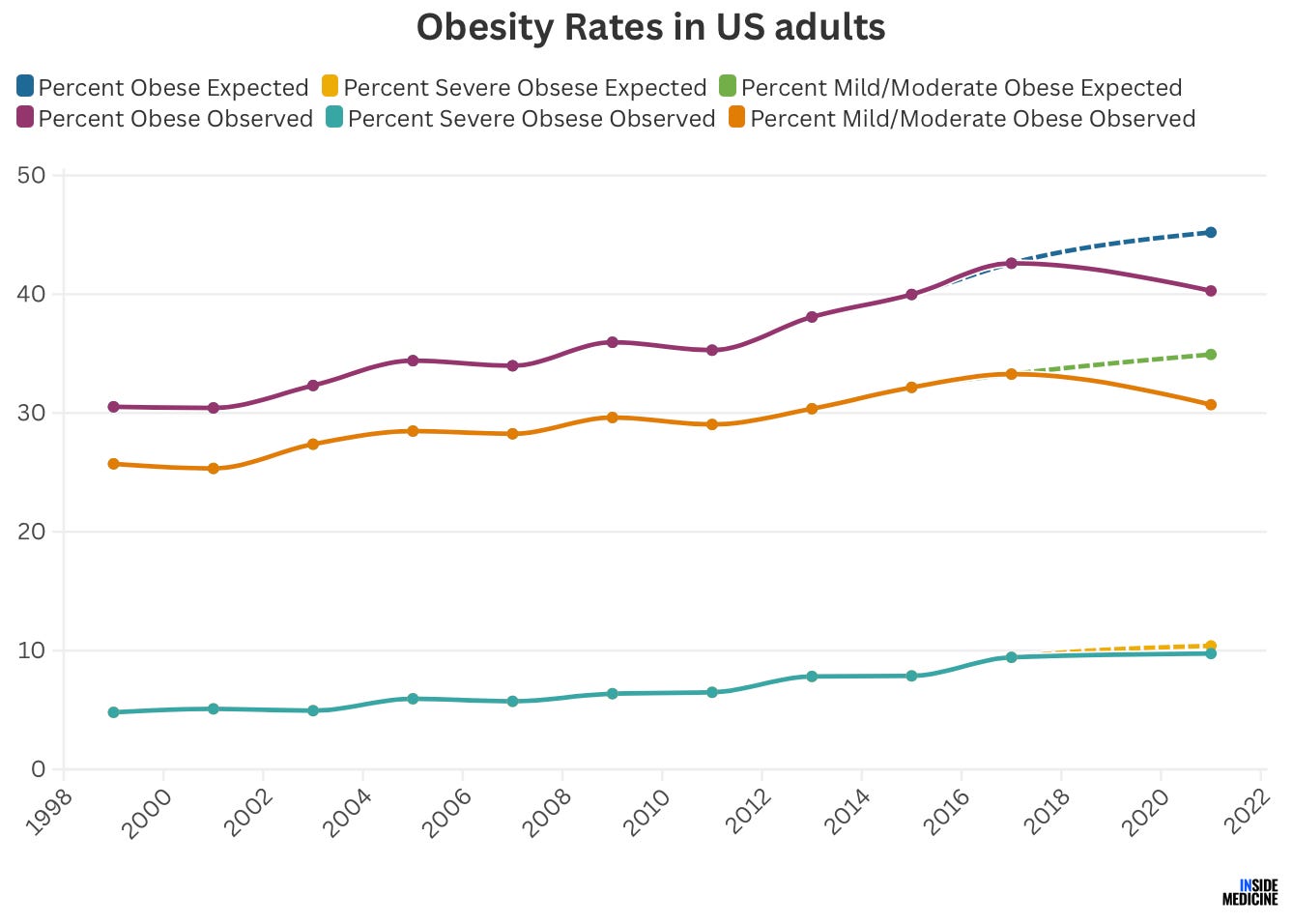

The data in question come from a CDC report which found that among adults aged 20 and older, obesity rates fell from 41.9% (2017-2019 data) to 40.3% (2021-2023 data). As mentioned, however, those two numbers were within the margin of error for the survey, so the difference was not considered to be statistically significant. Looking at Burn-Murdoch’s graph (which took data from the report and combined it with older data), it looks suspiciously “real” to me, but that is not rigorous enough by any means.

Does that lack of statistical significance mean that the difference between the two rates reported in a scientific study is just noise? Usually, but not always—and here’s why: CDC data analysts are very limited in what they are permitted to do with their own data. They are not permitted to make projections, the way my research colleagues and I would.

Look at the graph: Anyone can see that obesity rates have been on a steady rise since 1980. If you wanted to predict what 2021-2023 should have looked like based on historical trends, it would have been reasonable to expect that obesity rates would have continued their 40+ year steady rise, going from 41.9% in 2017-2019 to perhaps 44% by 2021-2023. When we are analyzing epidemiological changes, we often do not compare the present versus the past. Instead, we take historical trends into consideration and compare the present to rates we would have expected now based on consistent and stable trends over time. In other words, we should not compare 2021-2023 to 2017-2019, but rather to “expected rates for 2021-2023 based on previous trends.”

Of course obesity rates can’t go up forever. It’s always possible that things were destined to taper off. That’s why no model is perfect. On the other hand, a bigger survey could have tightened the study’s margin of error, making the latest obesity rate (40.3%) statistically lower than the previous one (41.9%).

So, while I’m not sure whether the decrease reflects a true statistical change, it’s incomplete for us to stop where the authors did, simply because CDC researchers were limited in what they were permitted to do with their own data.

Inside Medicine’s Benjy Renton and I looked at this a little more carefully. We went back to the original data and deployed a simple model to estimate what “expected” obesity rates should have been; that is, what the rates ought to have been if existing well-established trends had continued (see the dashed lines below). So, while the CDC compared the last two purple dots in the line graph below (for obesity overall), we would have advised that they compare the purple and blue dots.

Using our method, the differences might—or might not—be statistically significant. We are not sure, nor are we even sure that either the CDC or we are using the right statistical approach. The point is that the data look impressive enough to us that we can’t write it off “just because” one rather clunky methodology (sorry CDC analysts!) didn’t show a statistical difference.

2. Could the GLP1 drugs even possibly responsible for decreased obesity in the US?

To me, the crucial question is whether it would actually even be feasible that GLP-1 drugs could be behind a decrease in obesity rates in the US. The answer hinges on whether enough people have been taking the drugs for long enough to make a dent in the population-level statistics.

Spoiler: People who think it is not yet possible for GLP-1 drugs to have lowered the national obesity rate have either not done the math, done it wrong, or do misunderstand the literature on these drugs.

Let’s talk through the math.

For obesity rates to decrease, there must be fewer people with a body mass index (BMI) of 30.0 or higher. According to CDC data, in 2017-2020 (really 2019, because they didn't collect data in 2020), 41.9% of the population aged 20 and older (which is 250 million people) met the criteria. That equals 104 million people.

Some people have BMIs of 30, and others have BMIs of 32, 35, 40, 45, 50, or higher. But we are really interested in a subset here—the group of people with obesity whose BMIs were low enough in early 2021 that a little bit of weight loss could nudge them out of the obese category and into the overweight category (BMI 25.0-29.9). There were around 83 million people in that category in the 2017-2019 data. So, to get the obesity rate from 41.9% in 2017-2020 to 40.2% in 2021-2023, we need to find enough people with BMIs that were low enough in 2017-2020 that the drugs could take them out of the obesity category and into the overweight in just a few years. Specifically, we need to get the mild obesity rate from 33.2% to 30.6%. To do that, we need 6.7 million people in this target group (that is 8% of the target group) to have lost enough weight to change categories.

Data suggest that 22% of people in the overweight or obese category have used GLP-1 drugs. That’s 18 million people in our target group. Even if only half of these people have been on the drugs long enough to drop out of the obesity category, that’s 9 million people, well above our goal. Even if 25% stopped taking them and gained the weight back, we’d still reach our goal.

Some have pointed out that the obesity doses of the GLP-1s have only been approved since 2021, meaning some people who have taken them lost less weight. It doesn’t matter. Studies show that patients with diabetes (with an average starting BMI of 33.9) who started taking the lower 1.0mg dose of semaglutide, approved for diabetes in 2017, lowered their BMI by 1.6 points in just 30 weeks. And a study testing the 2.4mg dose of semaglutide (now approved for weight loss) found participants reduced their BMI by an average of 5.5 points in just 15-16 months.

In other words, there are feasibly enough US residents in the right BMI range who have been taking GLP-1s for long enough that it’s possible that the drugs are responsible.

3. Why did severe obesity (BMI of 40.0 and higher) go up?

While the rate of overall obesity went down, the rate of mild-to-moderate obesity (BMI 30.0-39.9) decreased, the rate of severe obesity (BMI 40.0 and up) actually increased by 0.5% (from 9.2% of adults to 9.7%). Some have pointed to this as a sign that GLP-1s are not responsible for the change.

That’s not necessarily the case. There are at least two reasons I can think of that could explain this finding.

It’s possible that people in the severe obesity category are slower to reduce their BMI. Patients who start taking Wegovy (semaglutide), for example, start at a very small dose and increase over many months. It’s possible that only the full dose helps them, and that it takes their bodies longer to respond.

An alternative hypothesis that occurred to me—and one I have not seen proposed elsewhere—is rather the opposite of what I just proposed. What if GLP-1s work so well for people in the severe obesity category that, in only 3 years, the mortality benefit of these drugs has started showing up in survey data. In other words, the reason that severe obesity rates went up in the most recent surveys may be that for the first time, there is a cohort of patients who otherwise would have been dead, but who now, due to GLP-1s, are alive to be able to fill out the surveys. It’s an astonishing possibility, but not an impossible one. All that would need to happen is for 1% of people in the severe obesity category to have dropped into the non-severe category (which we already know is doable) while 1.5% stayed in the category by virtue of having not died. Is this magical thinking? Not necessarily. The SELECT Trial found that participants with obesity randomized to receive semaglutide died less often than placebo recipients, around a 1% absolute difference (a 19% relative decrease) in 3-4 years. A new study indicates that many, many lives stand to be saved from GLP-1s.

4. Correlation is not causation.

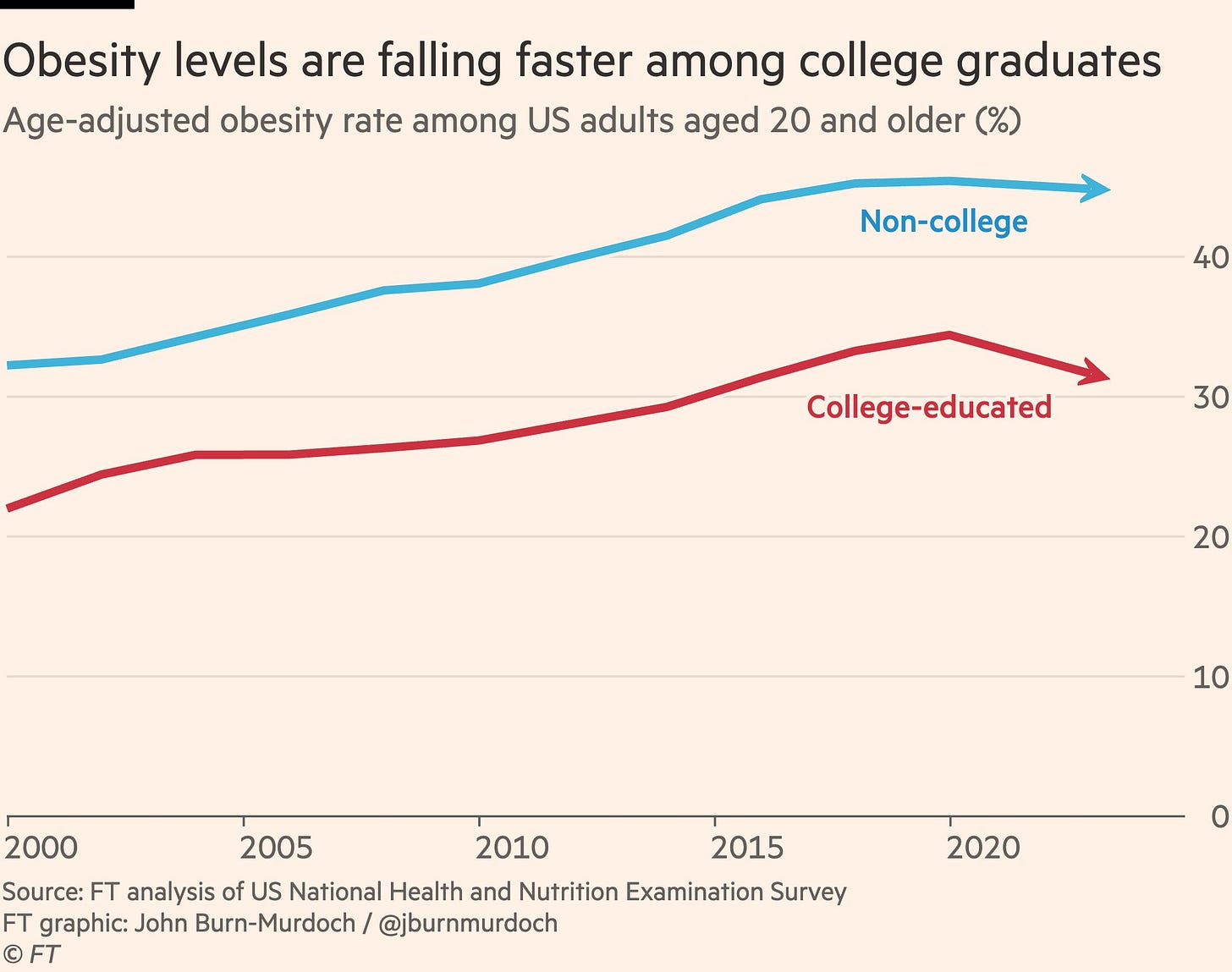

This is the one argument I can’t refute. The CDC data simply don’t address whether any decrease in obesity in the US is due to GLP-1 use. But there’s one piece of circumstantial evidence that leans towards GLP-1s as a contributor; the rate of obesity in college-educated survey respondents dropped, while the rate of non-college educated respondents did not. Who do you think has access to GLP-1s? Educated people with better health insurance. This finding also tends to undermine the view that Covid-19 had much to do with this, since obesity is a risk factor for Covid-related mortality. If the decrease in obesity were related to Covid-19, we’d see more decreases in non-college educated people (frontline and essential workers who could not stay home during the pre-vaccine era), and fewer in the college-educated group who could more often work from home.

Bottom line.

I’ve often said that when complicated questions arise and the data are not yet abundantly clear or interpretable, clinical insights can be especially powerful. Just about every time I work in the ER, I see patients who happen to be taking a GLP-1 (but who are there for other reasons). The weight loss is noticeable and impressive.

What I see in the CDC data and in my clinical practice tells me that something genuinely amazing is happening. The tide may finally be turning in the obesity epidemic—and it’s not like we haven’t been trying to deal with this problem for decades. What suddenly changed? We haven’t changed our food. We haven’t improved our fitness. Maybe, just maybe, it’s the meds, folks.

While the latest data don’t prove that the GLP-1 drugs are responsible, my belief is this: It’s not only possible that GLP-1s are playing a meaningful role in decreasing obesity rates in the United States; it is likely that they are.

Questions? Feedback? Please share them in Comments section.

Thanks again to Benjy Renton for help wrangling the data informing this post.

Thank you! Excellent analysis.

Continue compliments of Eric Topal

A 40-50% reduction of opioid overdose or alcohol intoxication with GLP-1 drugs among >1.3 million Americans with history of opioid or alcohol use disorders, respectively onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111