Is this monkeypox strain more contagious? What have we learned and how worried should we be?

It’s too soon to tell, but the rising number of suspected cases is alarming.

There is a case of monkeypox at a Boston hospital right now. There's another potential case in New York City. As of May 19th at 6:11pm, those are the only suspected or confirmed cases in the United States.

So far.

Many people are already worried that whatever strain of monkeypox is causing this outbreak is more easily transmissible than prior ones.

While that’s possible, we certainly don’t know that yet.

In favor of a newly more transmissible virus is the sheer number of rapidly increasing suspected and confirmed cases appearing simultaneously in multiple countries and in multiple cities around the world.

Right now, we know of 101 possible cases and 34 confirmed ones, spread across England, Portugal, Spain, Canada, Sweden, Italy, France, Belgium, and the United States. Prior to this outbreak, there had been 450 known cases in Nigeria since an outbreak in 2017, and a total of 8 cases in all other nations combined.

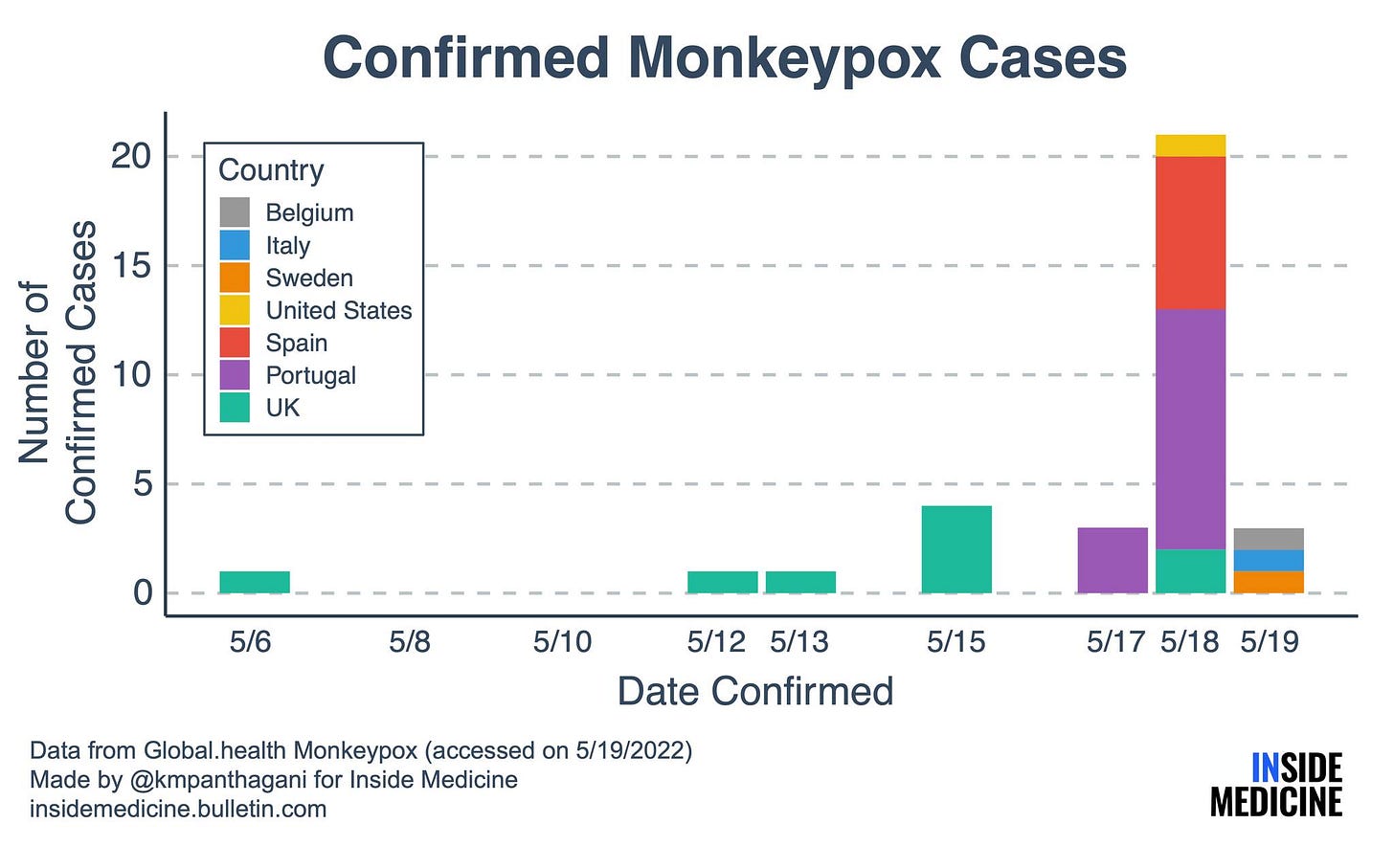

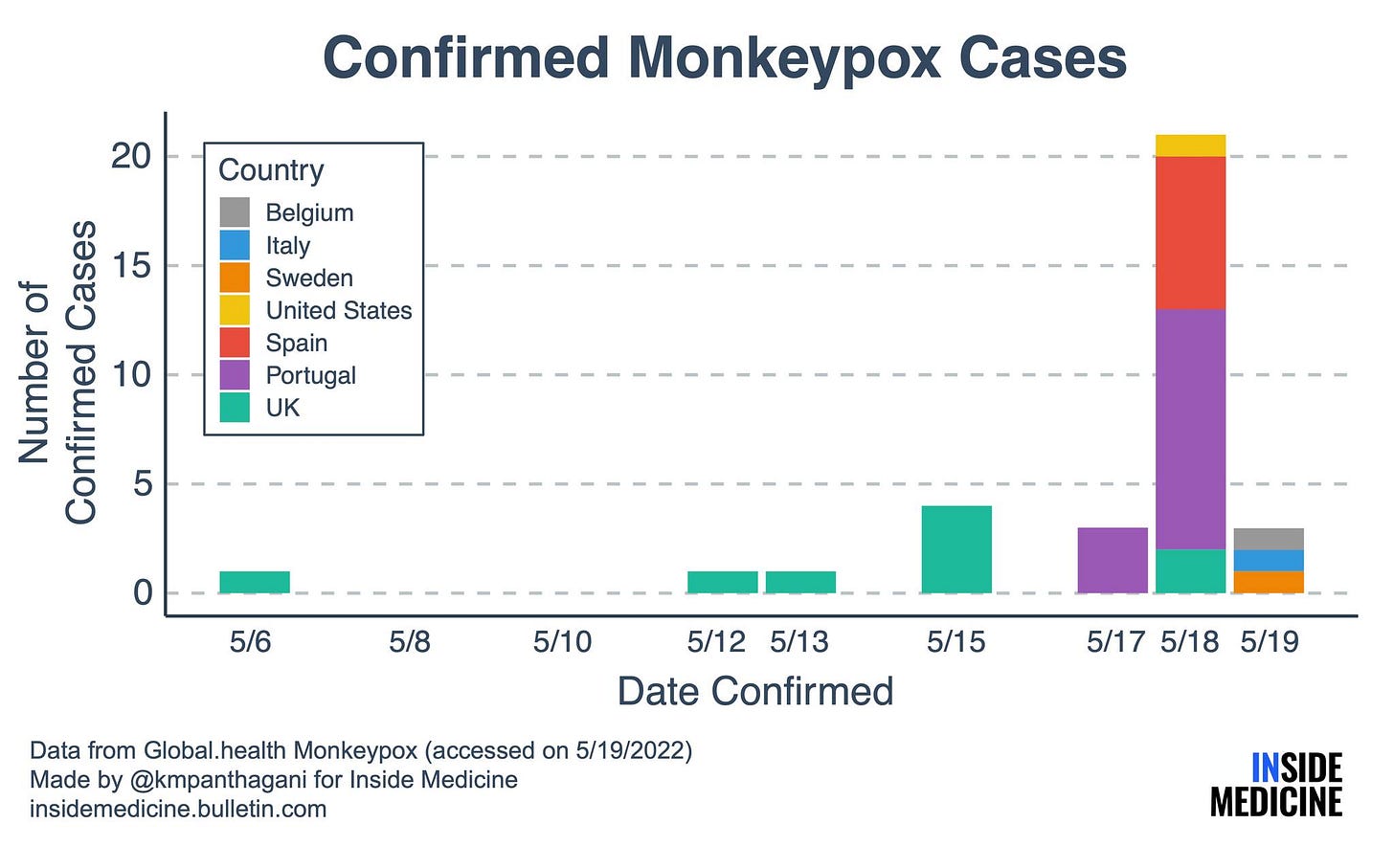

From the list above, there are at least 9 nations with suspected active cases currently. That’s an escalation, to be sure. A live Google document produced by Global.health, an open-access public health data repository, is tracking this (and serves as the basis of the graph created for Inside Medicine below).

Of the 101 suspected cases, 34 are confirmed. Data: Global.Health. Image: Dr. Kristen Panthagani for Inside Medicine.

Against the idea that this virus is more easily transmitted than earlier variants—say through smaller droplets or via the air—is that among the 89 cases being investigated for whom we know the gender, all 89 are males, a large number of whom are young and middle-aged adults. Public health agencies have reported that this monkeypox outbreak has been spreading in males who have had sexual contact with other infected males (or members of a shared sexual network). However, we do not know if that is true in some, many, most, or all of the cases.

Still, what we do know suggests strongly, to me at least, that monkeypox may still be primarily spreading through sexual contact, a known major mode of transmission. It could be that this virus has not gained any newfound stability in the air or in droplets—and that would certainly be welcome news—but that it is spreading with greater ease than usual (and therefore via more casual contact) in sexual networks, due to some genetic changes in the virus.

So while I’m worried that this outbreak may be different from previous ones simply because of how many cases are being reported in so many locales all at once, I’m cautiously optimistic that the lack of any reported cases in females so far means that this pathogen has not suddenly become airborne, more stable in smaller droplets, or that we previously did not recognize these as more important modes of transmission than they are.

•••

Here's a brief “monkeypox primer” that should answer many of your questions. This is based on reading I've done over the last couple of days and from speaking with a few experts who I know and trust.

What is monkeypox and what are its hallmarks?

Monkeypox is a virus, related to smallpox. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, monkeypox symptoms initially resemble other viral illnesses. Think fevers, body aches, fatigue. But four features make monkeypox stand out. First, swollen glands and skin findings. That’s what you’ll see if you Google “monkeypox images.” Lesions progress from flat to raised lesions, and eventually fluid filled lesions called vesicles, which eventually scab over. Second, monkeypox has a long interval from infection to the appearance of symptoms, ranging 5 to 21 days. People stay sick for a long time—up to weeks. Lastly, monkeypox is a lot deadlier than most viruses. While 10% of cases in Africa have been found to be deadly, the figure is a lot closer to 0% in regions with higher-resource medical care in more places. (Of known cases in the United States, none have been deadly.) Antivirals and immunoglobulins have been used to try to treat monkeypox, though the evidence to support this is thin. Also, those who have received a smallpox vaccine in the past are expected to have at least some cross-protection. Nevertheless, this is not a virus anyone wants to contract.

Where does monkeypox come from?

Monkeypox lurks in what we call an animal reservoir—that is, it mostly circulates in animals for long periods of time. In many cases the animals themselves are relatively unaffected by it. While monkeypox was first discovered in a cluster of monkeys being used in research in the late 1950s, it may mostly reside in another “order” of animals—rodents. Occasionally, monkeypox can jump from an animal to a human (“zoonotic infections”). When that happens, outbreaks are possible.

How does monkeypox spread?

The dogma has always been that monkeypox “does not spread easily” between humans. To be complete, here’s the CDC’s description on monkeypox transmission:

“The virus enters the body through broken skin (even if not visible), respiratory tract, or the mucous membranes (eyes, nose, or mouth). Animal-to-human transmission may occur by bite or scratch, bush meat preparation, direct contact with body fluids or lesion material, or indirect contact with lesion material, such as through contaminated bedding. Human-to-human transmission is thought to occur primarily through large respiratory droplets. Respiratory droplets generally cannot travel more than a few feet, so prolonged face-to-face contact is required. Other human-to-human methods of transmission include direct contact with body fluids or lesion material, and indirect contact with lesion material, such as through contaminated clothing or linens.” --The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

I’m sure everyone reading that had the same thought I just did. Did they just say that air-based spread occurs in “respiratory droplets that cannot travel more than a few feet”?

Sounds eerily familiar. Indeed, if monkeypox somehow turns out to be far more airborne than we realize—as we failed to realize soon enough with SARS-CoV-2—then we could be in trouble. But, as yet, I’m unconvinced. However, out of caution, for now we should assume that monkeypox is more easily transmissible than we’ve previously understood (even if that assumption ends up being false), whether through sexual contact or more passive exposures, either because of a change in the virus, or from a change in our ability to track infections and share data in real time.

•••

Are we on the edge of another public health crisis? Possibly, though it’s too soon to know. What investigators learn about the suspected and confirmed cases in the coming days and weeks hold the answers. The hard work of epidemiology and genetic research is underway.

If this outbreak turns out to be limited to male-male sexual contact, that might be reassuring for some people, and the opposite for others. But the rapidly increasing number of cases in people who are geographically far from any one particular hotzone, and among people who did not all travel to-and-from the same area tells me that the “usual” assumptions about how transmissible monkeypox is may not apply to this outbreak. And it bears repeating that all people, male or female, can be infected with this virus.

For more information, visit the CDC’s website here. We'll be following this story closely.

•••

❓💡🗣️ What are your questions? Comments? Join the conversation below!

Follow me on Twitter, Instagram, and on Facebook and help me share accurate frontline medical information!

📬 Subscribe to Inside Medicine here and get updates from the frontline at least twice per week.

Acknowledgements: Dr. Kristen Panthagani for identifying the data and creating the visualization; Dr. Angela Rasmussen, Dr. Carlos del Rio, and Dr. John Ross for input, and Global.Health for the data on these outbreaks.