HIV/AIDS infections and deaths continue to disproportionately affect Black people in the US.

We are back with a Monday Data Snapshot.

Last Wednesday was National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day. Why the special callout, when this virus has caused illness and mortality among all groups?

Let’s look at some data to understand why awareness of this issue is crucial.

According to the CDC, in 2019, 41% of new HIV infections in the United States were among Black people. This is despite the fact that Black people comprise around 13.5% of the US population.

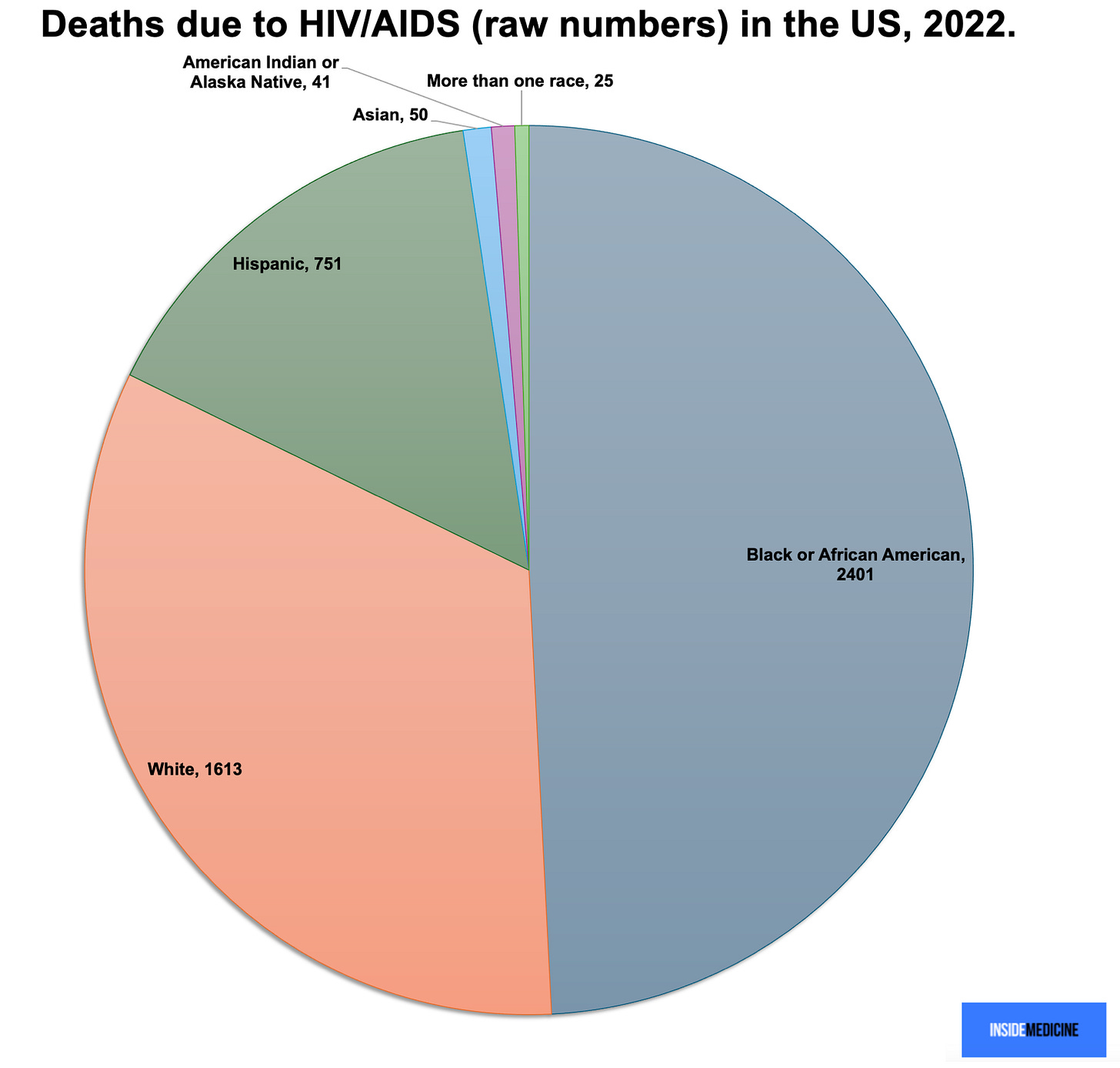

If that weren’t concerning enough, HIV/AIDS deaths among Black people are disproportionate to the share of cases. Specifically, Black people comprise around 13.5% of the US population, account for 41% of the new HIV infections, but (as of 2022), account for 49% of the deaths. (It’s actually just about 50%, but in these data, Hispanic-Black people are counted in the Hispanic category only.)

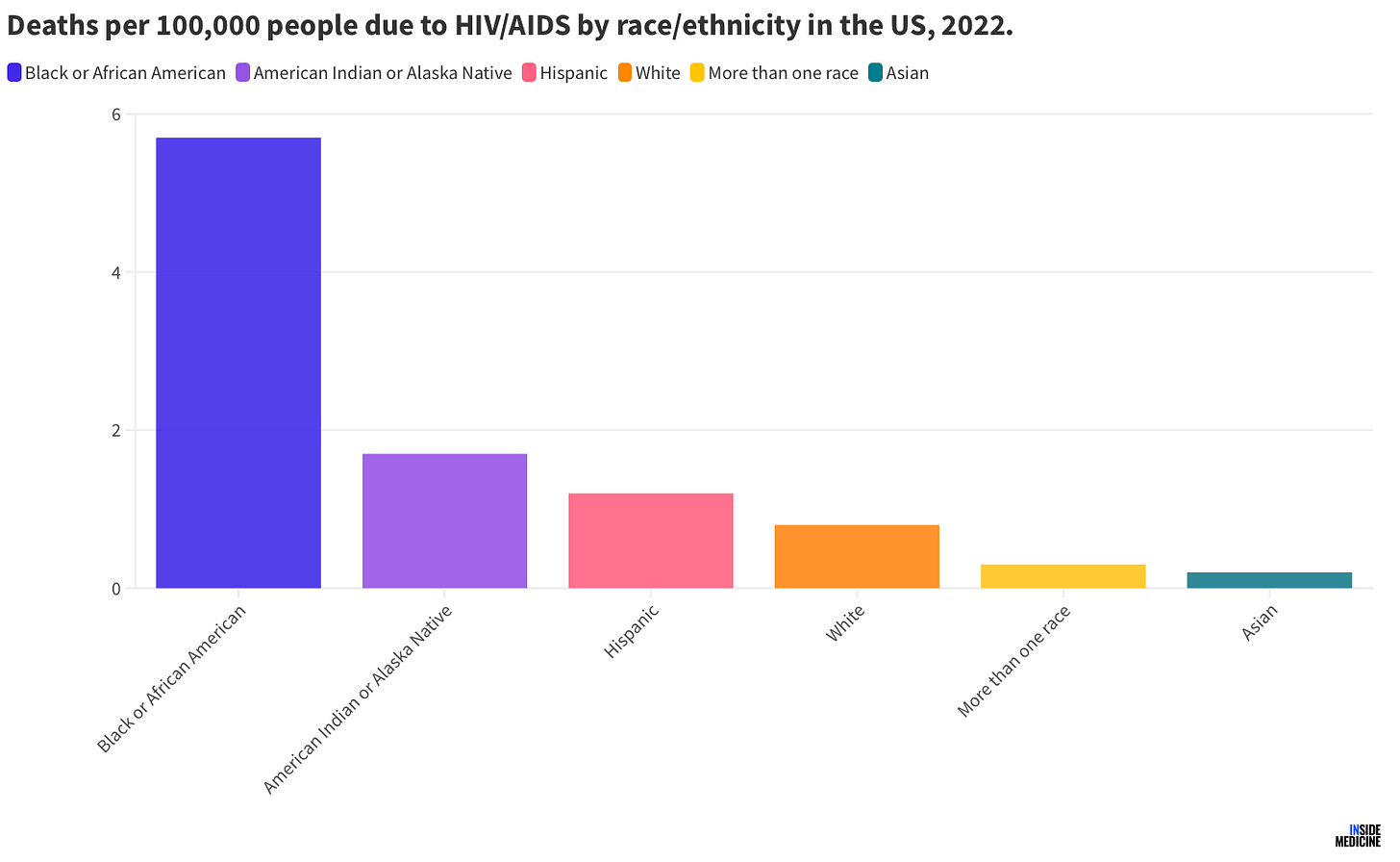

To give a sense of the per-capita effect, I graphed HIV/AIDS deaths by race/ethnicity in 2022 per 100,000 people. The disparity here is startling.

While HIV/AIDS deaths are dramatically down across the board since protease inhibitors were introduced in the mid-to-late 1990s, this disease still affects many people, especially overseas where access to medications remains a pain point for millions of people. (Although, shout-out to PEPFAR, one of the US government’s great achievements in global health.)

Nevertheless, you can see in the data why the CDC wants to continue to highlight this problem and devote resources to it. Thousands of deaths per year in the US due to HIV/AIDS is not acceptable, especially given how powerful our prevention and treatment tools are today. HIV/AIDS deaths peaked in 1995, at over 40,000, a staggering figure. So, while the reduction to around 5,000 deaths per year represents a massive victory for modern medicine and public health, given the tools we have today, the number should really be a lot closer to zero. Racial disparities/structural racism have a lot to do with the numbers being as high as they are.

A word on PrEP. Indeed, while many people are aware of how to prevent the spread of HIV (safe sex, avoiding unsafe IV drug use practices), I’m not sure how many general readers realize how effective pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is. (PrEP is when people who do not have HIV—but are at high risk of getting it—take anti-viral medications to prevent getting the infection. It is remarkably effective.) Sadly, the CDC reports that only 8% of Black people who would benefit from PrEP in the US actually receive it. Meanwhile, 23% of the overall population who would benefit gets PrEP. This reveals a genuine structural/systemic problem that is literally costing Black lives. Look, 23% uptake for a life-saving (and cost-effective) intervention is low and we should be doing so much better. But 8% uptake among the Black subset of that group is simply a scandal at this point.

PrEP is so crucial, that rates of use among the at-risk population is one of the major indicators that epidemiologists are tracking in the effort to end the AIDS epidemic. Meanwhile, for people living with HIV, medications can suppress viral loads to nil, making it virtually impossible to spread the virus.

Here are some related links for you to read and share in your networks:

Knowledge is power…Please share this one!

Please leave your questions and thoughts in the Comments section…

This is a cogent, important column recapitulating the well known disparities and solid data showing the ongoing disproportionality of HIV/AIDs among Blacks. As you correctly note, " Racial disparities/structural racism have a lot to do with the numbers being as high as they are."

I think as educated professionals, more civically engaged than most, it is time for you and all MDs to stop merely commenting on structural racism and do something about it! An excellent, dramatic first step would be to mobilize our profession to have our elected officials eliminate our racist second class health care system for the poor -Medicaid. Newly formulated legislation would allow it to be rolled into Medicare including all the best and most expansive range of services demonstrated in the various states while raising reembursements to Medicare levels. While this would not meet the primary prevention of HIV/AIDs needs of poor and minorities, it would greatly improve "secondary and tertiary prevention."

There are a remarkable number of people who come into the emergency room with full blown AIDS who cannot organize themselves enough to take one pill a day, even when it is provided free of charge.