HHS cuts: the method was the madness.

While HHS could be more efficient, yesterday's cuts felt more like gleeful arson than a controlled burn.

Inside Medicine is 100% supported by reader upgrades. I hope you’ll consider pitching in if you’re able so that this work can continue. (And if you can’t due to financial considerations, just email me and it’s all good). Thank you!

Yesterday, the Trump administration terminated around 10,000 HHS employees, as had been feared. In its implementation of the anticipated “Reduction In Force,” entire divisions were axed. Respected leaders were terminated. As Emory University’s Dr. Carlos del Rio told me, it felt like “the Kristallnacht of public health.”

Mostly, I spent the day trying to wrap my mind around what has been lost and speaking with current and former HHS employees who were clearly rattled, if not devastated.

But, at some point, I also heard from a few people in my orbit who were less doomsday about everything. After all, they argued, is there not too much bureaucratic bloat in some of these agencies? If somebody tasked me with reorganizing HHS to maximize efficiency, would I not be able to make some major improvements? Sure, I said, but this is not how I would have gone about it.

And that is what I want to say to you today. The effects of yesterday’s cuts on the health of Americans and on medical and scientific progress are unknown, and they won’t be for a long time. We may never know the true impact of these cuts, because we don’t know what crises lie around the corner nor whom we may come to regret letting go.

But even if the impact on American health is minimal—even if somehow things were to get better from here—that will never justify the cruel manner in which these reductions were implemented.

Before getting to that, and without conceding a point, I want to share a lesson from my childhood. When I was ten years old, I lived through the deadly and destructive 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake in San Francisco. In addition to far worse things, the earthquake severely damaged the Embarcadero Freeway. Instead of rebuilding the structure—a major eyesore— the city decided to tear it down permanently. At the time, many experts bashed the decision, anticipating that the move would cause tremendous and permanent traffic gridlock. That simply never materialized. People changed their routes and public transportation use suddenly increased. It was an early lesson for me: even experts don’t always know what will happen. Sometimes good outcomes can come from seemingly bad things.

So, we have to acknowledge that the practical results of yesterday’s HHS cuts might be terrible—or, in the fullness of time, they might not be. While it’s easy for me to assume that everything will be awful, the truth is that I do not know what will happen. This was the point that these more moderate voices in my inbox were making.

The messaging and the methods were tells…

But I have two problems with how all of this went down, and they are not minor. And, as I wrote yesterday, my concerns are not just me being a softie at the expense of the real issues—i.e., data and outcomes. This is about a brain drain. Treating dedicated HHS employees with disrespect today will not help us recruit the best and brightest tomorrow—which is what we need, regardless of the size of its workforce.

First, there does not appear to have been a serious inquiry into how to tighten the belt across HHS. If DOGE somehow studied all of this adequately in the last two-plus months, they certainly have not shown their work, nor did they engage, as far as I can determine, the top experts at the agencies best positioned to do such difficult work. That’s insulting to everyone involved, including the taxpayers. Look, if, for example, combining two agencies into one is really better, why not lay out the argument and justifications? Apparently, HHS employees and the public are just not important enough to warrant any such explanations. That does not sit well. It tells me that DOGE does not care to persuade experts, nor the American people, on the merits of what it has done. It does not believe it is accountable to anyone. It simply wishes to demonstrate that it can exert its vengeful power and leave everyone else to clean up the mess left behind. Again, if the administration genuinely cared about how this will affect our health outcomes and our medical and scientific systems, it wouldn’t be terminating people without giving anyone ample time to arrange for the smooth continuity of important projects.

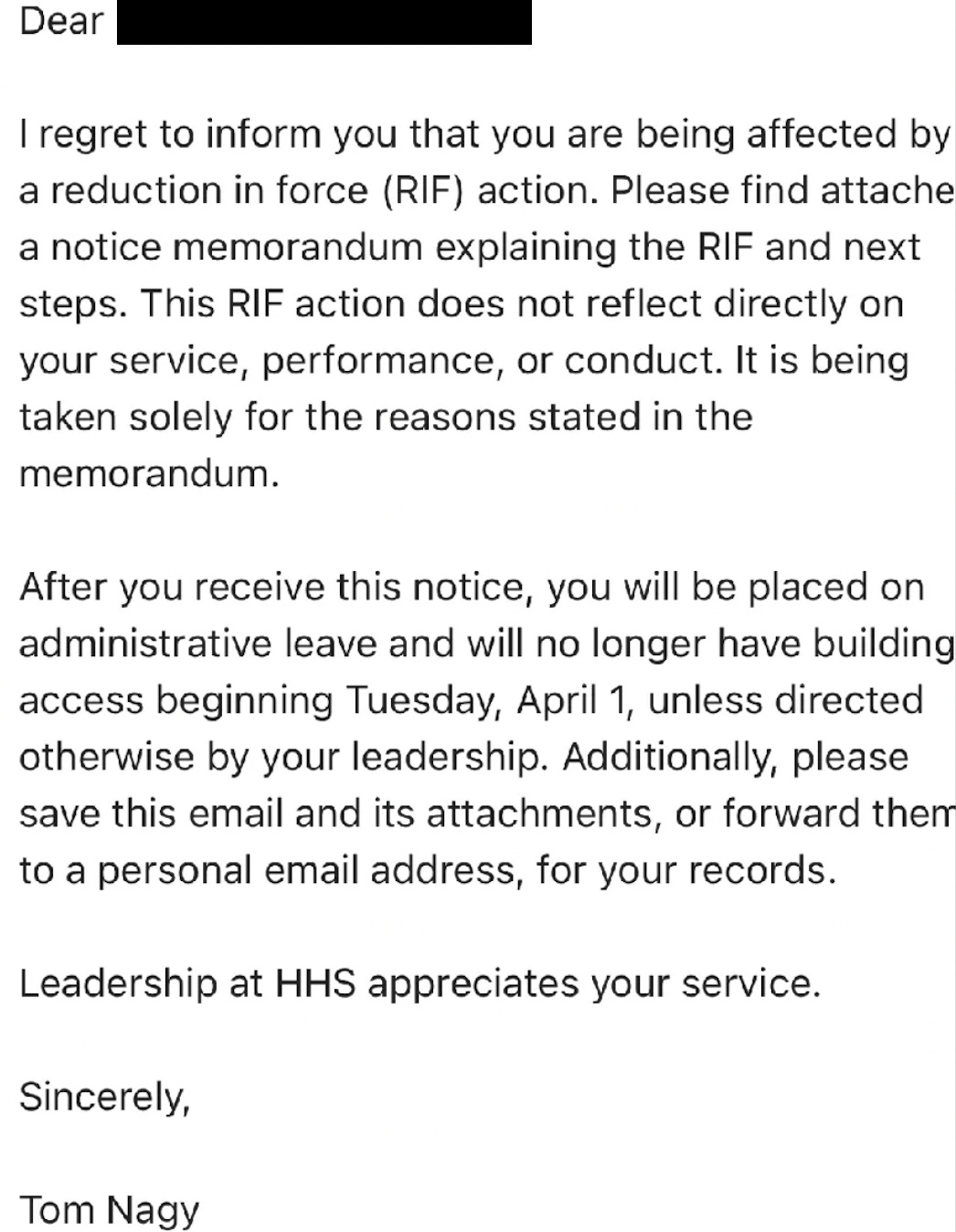

Second, the way HHS employees found out they had been RIF’d was exceedingly cruel. There is a difference between a controlled burn and gleeful arson. What we saw yesterday felt like the latter, as we’ve seen throughout this administration. Many have said the “cruelty is the point.” Perhaps. At a minimum, the administration doesn’t seem particularly bothered or concerned with it.

“You don’t RIF someone by badging them,” a former HHS employee told me. Yes, RIF and badge are now verbs. As in: “the entire purchasing division got RIF’d,” or “a bunch of people got badged”—meaning that the way HHS employees found out that they’d been terminated from their jobs was that their ID badges failed to scan at a security checkpoint yesterday morning.

I’m sorry, but that is just fucked up.

Anyone who is responsible for how this went down should not be able to look themselves in the mirror anytime soon. Below is a picture taken yesterday by an FDA employee and Inside Medicine reader. It shows over a dozen people waiting to speak to security after their badges didn’t work. Can you imagine finding out you’d lost your job this way?

In other cases, terminations were sent out by HHS bureaucrats. “One of the RIF notices they sent out listed a manager for staff to reach out to who had passed away four months ago,” one HHS source told me. In some instances, some higher-ranking employees were offered half-hearted reassignments elsewhere within HHS. For example, some leaders at CDC were offered positions in the Indian Health Service that had nothing to do with their expertise. Imagine being a disease modeler in Atlanta and being told you could take a job in Alaska that has nothing to do with that kind of work or else quit. And yet, I can confirm that this is precisely what happened yesterday. Actions like these do not reflect a sincere effort to redeploy HHS workers more efficiently to help the American people confront our health challenges. They reflect a cruel indifference to the human cost.

Another former HHS employee echoed the sentiment to me. If you have to make cuts, “you do it with grace and style. This [DOGE] crowd is doing it in a mean-spirited way, which no one has ever experienced before.” Another former HHS employee said some cuts to reduce redundancy and bureaucracy might have been reasonable but that they were done “in the most ungracious way.”

Meanwhile, RFK tweeted “This is a difficult moment for all of us at HHS. Our hearts go out to those who have lost their jobs.” If he felt that way, he could have overseen a humane process. Instead, he continued with a justification: “But the reality is clear: what we've been doing isn't working.”

We can debate the merits of whether we are actually sicker than we’ve been in the past, but I don’t see where cutting 10,000 jobs gets us closer to our potential. Again, could I envision a world in which some of these individuals were redeployed? Is it possible that a few thousand needed to go to make room for those who could better achieve newer priorities? Perhaps. But I have trouble believing that 80,000 HHS employees are too many, and that 60,000 is just right.

Nor is this a smart or efficient way to save taxpayer dollars. Remember, employee salaries account for less than 5% of federal spending. That might be news to Elon Musk; when he bought Twitter, employee compensation represented nearly 80% of the company’s expenses. This is an example of how the private and public sectors are rather different. If you’re trying to save taxpayer dollars, I would posit that targeting the roughly 0.15% of the federal budget that is spent on HHS employee salaries is unlikely to make much of a dent. But what if another pandemic happens that we could have prevented with a fully and appropriately staffed HHS workforce? That would be costly.

Lastly, I have spent time reflecting on whether “my side” (the Democrats) was ever going to do the hard work of reforming or modernizing HHS. If former Vice President Harris had won the election, were my colleagues who would have worked in her administration really going to make big and important changes in HHS? Or were we going to perpetuate the status quo?

It is painful to admit, but it’s likely we would not have done anything significantly different, and that’s on us. However, if we had (as my friend Dr. Katelyn Jetelina reminded me yesterday), we could have done so responsibly, giving time and runway for people to make appropriate plans—both to assure the continuity of the work of the American people and to give HHS employees adequate time to make other plans. In other words, we would have insisted on civility and dignity, not cruelty.

If this experience has reminded me of anything, it’s that if you don’t do something yourself, someone else might do it—and much worse. Inaction comes with its own perils. We, on our side, need to remember that in the future.

Bearing witness…

What follows are a few miscellaneous items that I wanted to share from yesterday’s “bloodbath,” just to document what happened, and the callous indifference (at best) with which DOGE enacted these policies.

A bizarre encounter at the FDA: One FDA employee spotted what she thought was a DOGE employee (but is not sure)—a twenty-something male in all black and red sneakers. When she went to the cafeteria to grab lunch, she noticed the person in front of her seemed “out of place.” He made awkward small talk and then said, “Yeah, so today is going to suuuuuck.” Then, according to the source, he shrugged and nonchalantly said, "But what are you going to do?" After that, he paid for his food and disappeared.

Below are screenshots of emails and announcements shared with Inside Medicine by HHS employees at the NIH and FDA.

Mourning lost colleagues:

An RIF notice:

An NIH email indicating the chaos caused by the termination of the entire purchasing department at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, where Dr. Anthony Fauci was the long-time Director:

An announcement at FDA conveying the news that the entire library staff had been terminated:

That’s all for now. If you have information about any of the unfolding stories we are following, please email me or find me on Signal at InsideMedicine.88.

Thanks for reading, sharing, speaking out, and supporting Inside Medicine! Please ask your questions in the comments.

An epidemiologist colleague was fond of saying "When I do my job right, nothing happens." In public health, we don't know whose lives we save, and it can be hard to quantify them. But our work does save lives. Eliminating entire programs? Real lives will be lost, but only some of us will know.

All public health is local, is a popular mantra in public health circles. But the lion share of funding for local public health doesn't originate from State Governments. The federal government, specifically HHS, USDA, and DHS financially support local public health efforts. Cutting federal programs that support local public health, endangers the lives and the livelihood of millions of Americans. We are currently in the middle of a measles epidemic. What specifically is President Musk and his Health Team doing to prevent and control its spread?