Field Notes: Two questions about headaches that ER doctors always ask—and the one they don’t, but should.

Headaches are a headache. But even most severe ones are benign, rather than tumors, strokes, or signs of carbon monoxide poisoning. Still, if you go to an emergency room with a headache, your doctors will consider all those possibilities and more. Eventually, you’ll be asked versions of these two questions:

"Is this the worst headache of your life?"

"Did the headache begin suddenly?"

You’ll be asked others, but those two questions will almost certainly come up. Why? Because the medical literature tells us that if the answer to either question is yes, it could be indicative of spontaneous bleeding from an artery found along the spidery middle layer of the membrane separating your brain from the outside world. The implications of these “subarachnoid hemorrhages” range from benign to life-threatening.

I’ve diagnosed many subarachnoids, as we call them for short. Most have been mild and did not require neurosurgery. A few were serious. Had we not diagnosed and treated those ones, the patients might have gone on to have far worse episodes, possibly leading to permanent neurologic damage or death.

But there’s one headache feature that I’ve found is highly suggestive of a subarachnoid hemorrhage, and it’s one that we didn’t learn in school or residency: the sudden sensation of being the victim of trauma. Patients literally say things like:

“I actually thought I’d been hit in the back of the head by a baseball bat. But nobody was there.”

“I was shopping, and a shelf fell on my head. Except it had not. I was so confused.”

“It felt like someone was pulling all of my hair as hard as they could.”

I’m not aware of any literature studying the performance of this question as an indicator of a subarachnoid. But when a patient volunteers that they momentarily believed that someone or something had physically hurt them—only to discover that the pain was completely internal and spontaneous—my concern that a subarachnoid hemorrhage has occurred increases dramatically. (One exception is the “I feel like my head was in a vice” description of a headache. That one is quite common, and it must be what many migraines feel like. However, it’s a different pattern than the sudden attack/trauma stories above, if you think about it).

More on subarachnoid hemorrhages and how ER doctors think.

(Note: I am reticent to discuss a relatively uncommon condition here in my newsletter. I do so because it’s illustrative of how ER doctors think. I am not trying to make you all paranoid!)

Subarachnoid bleeds most frequently occur when a weak area of an artery—an aneurysm—ruptures. Sometimes a small rupture occurs. These “sentinel bleeds” cause tremendous pain but clot off before any significant damage occurs. It’s my job to identify these self-contained subarachnoids, so that the aneurysms needing neurosurgery are identified and treated before a much larger and more devastating bleed happens.

And in general, an ER physicians’ job is sorting out which patients have “dangerous headaches” including subarachnoids, and which ones have bothersome headaches which need symptom control, but no further action. Again, most headaches (even extremely painful ones) are benign. But headaches that are different from anything a patient has previously experienced should be checked out.

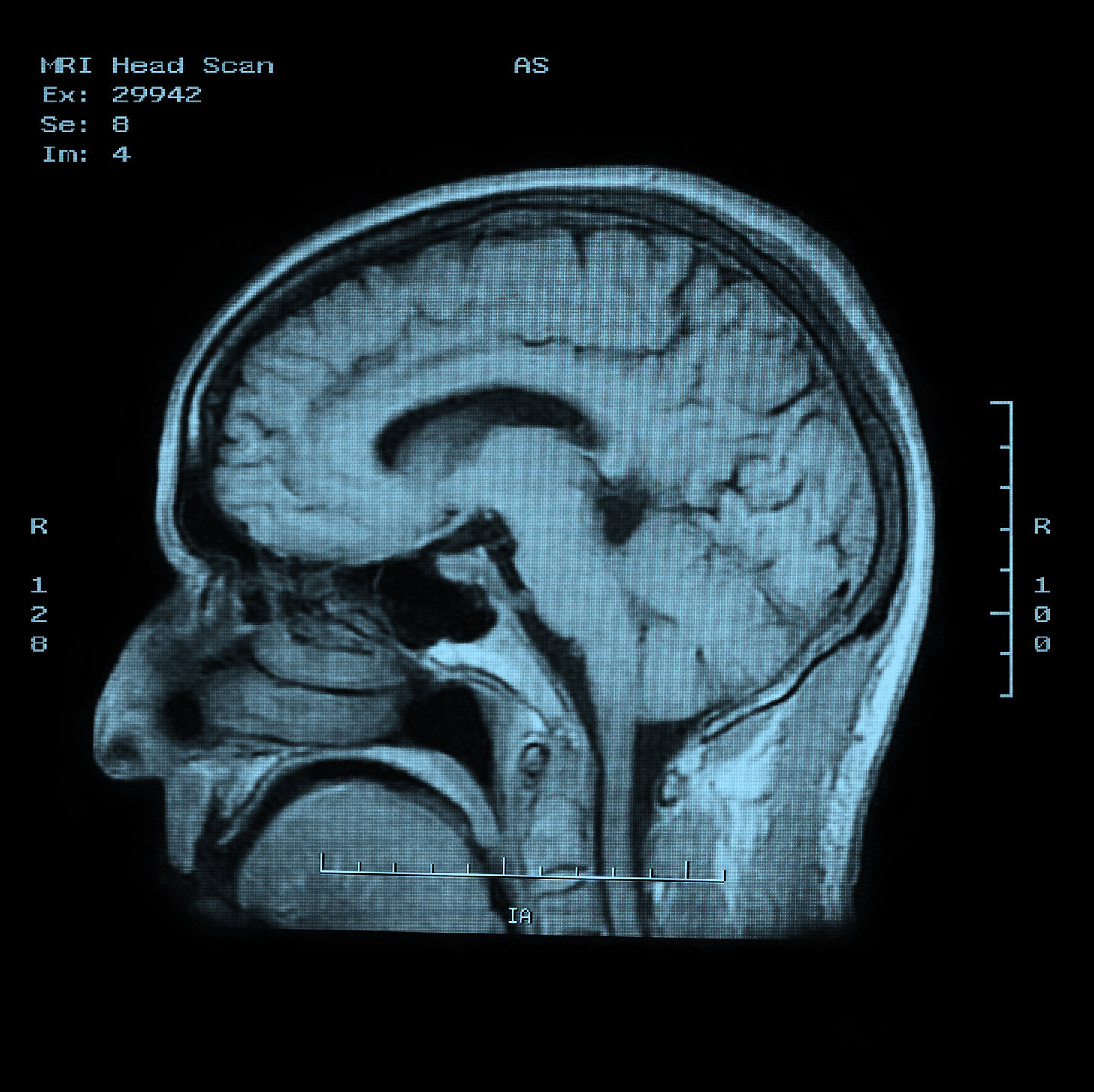

Fewer than 1% of patients who come to the ER with a headache have a subarachnoid hemorrhage. If we ordered CT scans or MRIs on everyone with a headache, the system would break down and patients wouldn’t benefit. There aren’t enough scanners and not enough radiologists to interpret them. The system would grind to a halt, causing delays in diagnosing other time-sensitive conditions. Plus, we’d be harming patients by scanning all comers with headaches. Yes, the scans are low risk (though they add hours to an ER visit), but there’s radiation to consider, and the harms stemming from false positives (i.e., findings which look like disease, but are not). False positives often lead to further tests, leading to “medical misadventures.” Occasionally, a rare but significant complication occurs, which is particularly tragic when the procedure that caused it was unnecessary in the first place.

The goal is to only scan perhaps 10% of ER patients with headaches, and yet never miss a single dangerous condition. Doing this is a huge aspect of emergency medicine as a cognitive discipline.

Back to the “two questions" and the one we never ask.

This brings us back to the frontline and those two fateful questions. Textbooks teach that yeses (“worst ever” and “sudden onset”) indicate the possibility of a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Here’s the problem. We don’t reveal the agenda behind these questions when we ask our patients about them. Patients don’t know what we mean or why we are asking. They answer yes because they correctly sense that we are asking loaded questions, and they want us to take their pain seriously. For example, a patient with chronic migraines might say they’re having the worst headache of their life—but that’s not because they’re worried about a new life-threatening diagnosis and are hoping to have a CT scan. They said yes because this headache is tied for first with 100 others they’ve had. It’s rational for them to say yes to the “worst ever” question because they believe that it’ll mean pain medications will arrive sooner. And, hey, it might.

The “sudden onset” question is also problematic. In a sense, all headaches began suddenly. One minute it wasn’t there, the next it was. But that’s not what we mean. We want to know whether a headache went from 0 to 10 (10 being the worst pain imaginable) in a matter of seconds or minutes, or hours. If the answer is seconds (often called a “thunderclap headache”), the needle moves towards subarachnoid hemorrhage.

For doctors, another problem is that the answers to the two questions don’t have enough power to rule out a subarachnoid diagnosis. Plus, there are many other features that somewhat increase the likelihood that a headache is a subarachnoid, and others that decrease the likelihood. But in my experience, none are reliably make-or-break. Sure, some characteristics (like pain in the back of the head) are more common in subarachnoids. But so many patients with migraines have similar pain. The location and character of a headache just does not alter my sense of the odds by enough to be actionable (i.e., to change whether I think a CT scan or MRI is needed).

Notice that so far, I’ve talked about information that patients volunteer. I haven’t said that I ask my patients about the illusion of trauma. In fact, I don’t ask my patients anything as direct as “Did you feel as if you’d been assaulted, but had not been?” That type of leading question would probably fail. It sounds bad to have been assaulted. I worry that if I asked it so overtly, patients would reflexively say yes, as they often do when asked the “worst ever” and “sudden onset” questions.

Instead, I ask a specific and paradoxically vague question: “What did it feel like in the moment that you first noticed the headache?” Usually, patients describe a headache that started somewhat mildly, but then increased drastically over some period, reaching such an extreme that an ER visit was necessary. But very occasionally they say something like, “Out of nowhere, I felt like someone hit me in the skull with a brick.” When they say something like that, there’s very little that will dissuade me from getting a STAT scan of their brain.

I find it interesting that the sensation of physical trauma in the absence of physical trauma is rarely if ever discussed in the medical literature as a sign of a subarachnoid hemorrhage (at least, not that I can recall). Maybe that will change. But for now, looking out for this feature falls into the “art of medicine” as I personally practice it, not the science of medicine. It’s something I teach my students and residents to watch out for and, I think, has helped me diagnose this relatively unusual but important condition.