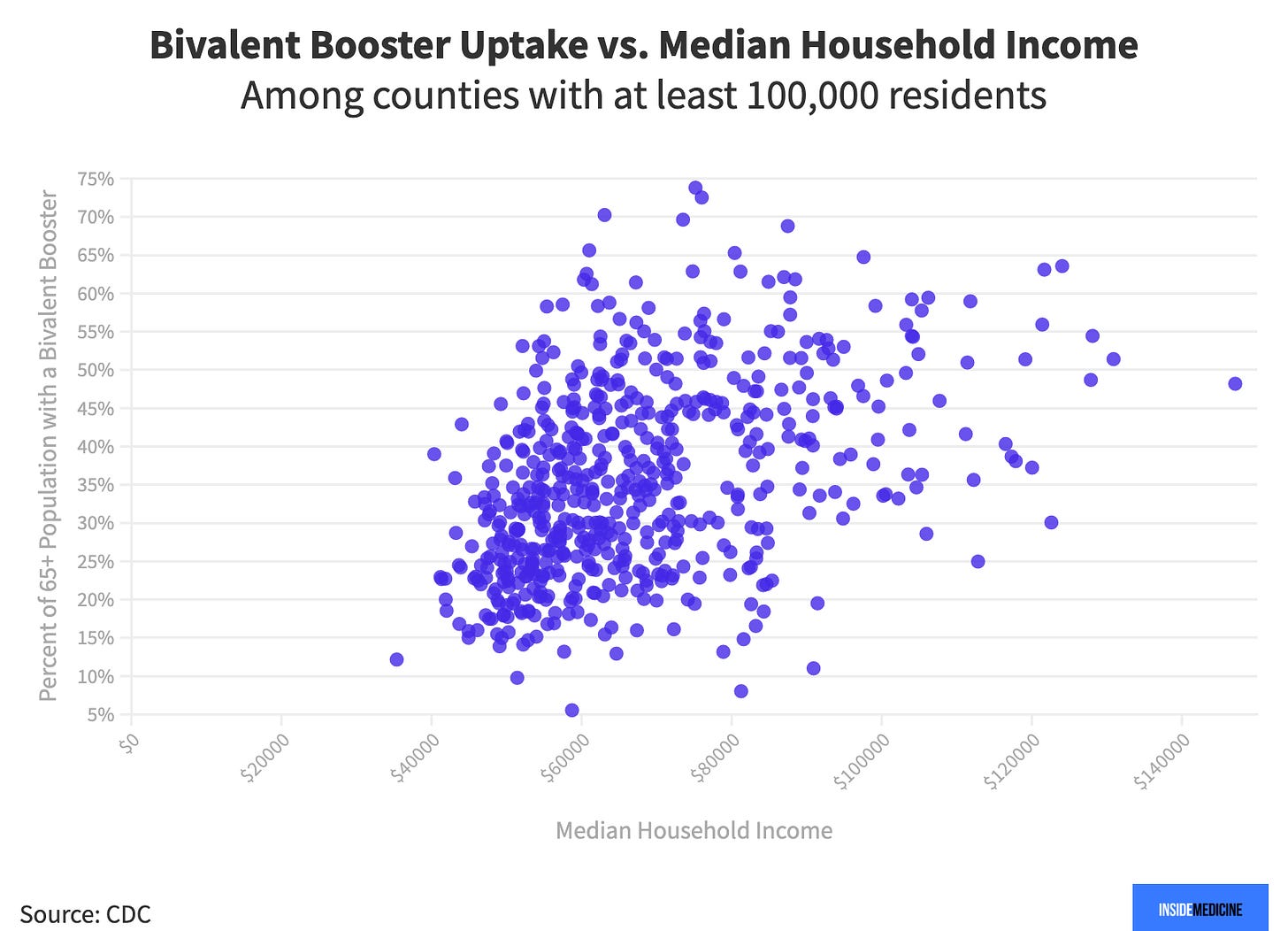

Data Snapshot: Bivalent booster by income level and insurance status.

Systemic inequities play out yet again.

Recently, I asked a patient in his 60s with a few medical problems whether he had gotten the Covid-19 bivalent booster yet. “I didn’t even know I’m due for one,” he told me. He thought his 3rd dose, which he received over a year ago, was enough. He basically missed the memo on his eligibility for a 4th dose last spring, as well as the new bivalent booster which came out this fall. It was a good reminder that not everyone keeps up with the latest Covid-19 policy. I told him that based on my assessment of the data, someone like him would benefit from the bivalent booster. He said he’d get boosted in the coming week.

In addition to other inequities on vaccine uptake that we know about (race and ethnicity being major ones), other factors contribute to low vaccination status. Having a lower income and a lack of health insurance are each markedly correlated with not being vaccinated against Covid-19.

This is an unforced error, a failure of the public health system on messaging and access. And it’s not a money thing—the United States government decided early on that Covid-19 vaccines would be free to everyone. For some, access was an issue (although over time that has become less of a prominent factor). For the uninsured, the healthcare system is remote and often unfamiliar—a monolithic “thing” they don’t interact with routinely. That means that even though Covid-19 vaccines have been free and available for all for almost two years, uninsured people are less likely to have received them. That story is once again playing out with the bivalent booster.

Today’s Data Snapshot was collated from CDC data by Inside Medicine’s Benjy Renton. It illustrates bivalent booster uptake disparities dramatically. Once again, our system seems to “tax” those without access—those who live in poverty and/or without health insurance. Again, let’s focus on adults ages 65 and over, the group that benefits the most from boosters.

All told, US residents with higher incomes are more likely to have received a bivalent booster, while US counties with the highest rates of insured people also have higher rates of uptake. That means poor and uninsured people who get Covid-19 stand to be more likely to be hospitalized. As ever, being poor and uninsured turns out to be rather costly.