Nearly a year ago, I started using OpenAI and ChatGPT, both in my work as a physician and researcher, and also outside of work.

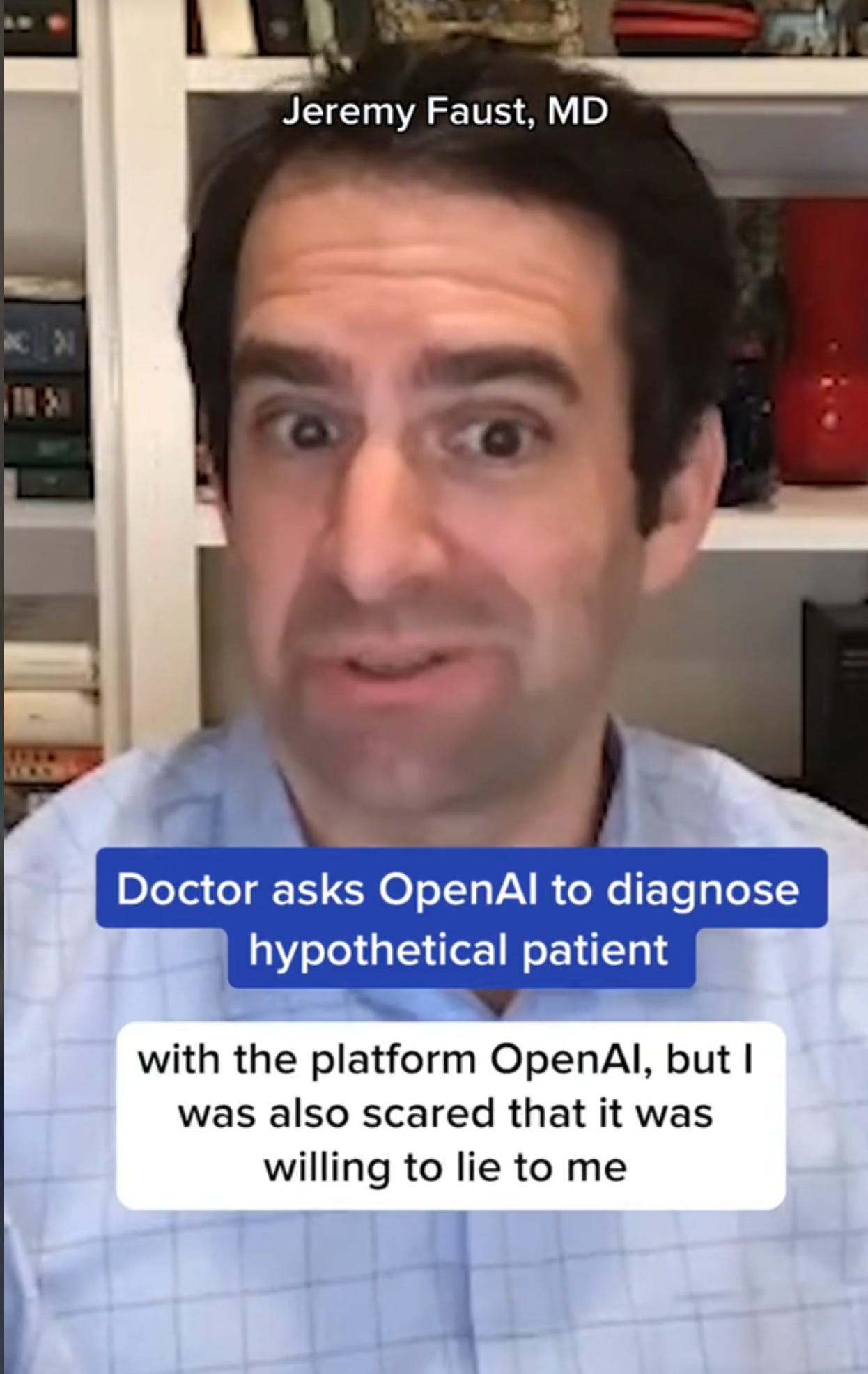

The first time I used an AI interface on my home computer, my jaw hit the floor. I was blown away with the power of the tool, but also a little disturbed by some aspects of it. OpenAI was able to answer some interesting medical questions I asked it. But it also lied to me, as I wrote here.* In fact, a video I made for Medpage Today about that experience went completely viral on TikTok (unbeknownst to me at first, because I didn’t actually post it). The video eventually got 2.3 million views.

Somebody thought all of this made me an expert on AI in medicine, and so I was invited to give a “grand rounds” on the topic, which I am delivering to a Harvard hospital later today. The truth is, when I was asked, I was hardly an expert in this. However, in the intervening months, I have become pretty experienced using AI for a variety of purposes, and I now consider myself quite adept (if not exactly a true expert) at using ChatGPT. What I mean is that I have gotten good at a skill that is called “prompt engineering.” That is, what you get out of ChatGPT depends greatly on how you use it—not just knowing what to ask, but how to ask it. Phrasing matters, as does the starting information that you give it.

To test this, I’ll show you an old joke we tell in the ER. A man shows up in triage with an elevated heart rate—110 beats per minute. If you don’t have the right information, you might think he has a dangerous medical condition. The trick is to figure out that the reason his heart rate is up is that he just ran from the parking lot because it’s cold outside. His heart rate is up not due to a heart problem—but due to exercise.

ChatGPT will figure this out if you give it the right prompt. Check it out (notice the verb change in the second attempt):

There are a million versions of this.

Largely, I use ChatGPT as an ultramodern Google (especially now that version 4 can check the internet.

But I’ve also had a handful of memorable “conversations” with it. I’m not sure if I’ve revealed this publicly before, but a term that I coined and introduced in a Lancet Infectious Diseases commentary on Long Covid I wrote earlier this year was the result of a collaboration between me and a freakin’ chatbot. I had come up with an idea and I wanted to know if this notion had a name already. Google and PubMed searches came up empty, as did a read-through of a few medical texts. I called up my friend Dr. Craig Spencer, who has a flair for medical history. He also knew of no official term for what I was describing (but suggested that I was, in effect, describing Koch’s Postulates in reverse—a nifty idea he let me use in the essay without attribution). My idea was that if a treatment can be shown (in a high quality clinical trial) to improve outcomes compared to placebo for patients who have a contested illness—that is, a new condition whose definition or even existence remains hotly debated—that is actually strong evidence that the condition really exists, and that the definition in use for the study was at least good enough to be able to find such an effect in the study population. After just a few exchanges with ChatGPT, a term showed up on a list of possible suggestions for this concept: therapeutic validation. So, now you know the story of how the therapeutic validation principle made its way from a concept I thought of while exercising, to a conversation with an AI chatbot, to a named entity appearing in a major medical journal.

Research updates.

As soon as ChatGPT went live, clinical researchers and medical educators started having a field day, racing to publish anything and everything imaginable on related topics in medical journals. Can AI answer patients’ questions? Can it correctly find reliable sources/references? Can ChatGPT make tough diagnoses? Heck, can it pass the medical boards?

The upshot is this: Yes to all of that. But one thing that I think has not yet made its way into the public consciousness is how vastly superior ChatGPT-4 is to its recent predecessors, ChatGPT-3 and ChatGPT-3.5. (ChatGPT-4 costs money.)

Here’s a quick update from my trip down research lane. These studies are limited to papers appearing in the JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association) network.

Accuracy of chatbots citing medical journal articles.

ChatGPT 3.5 was terrible at this, with an error rate of 79%. GPT-4 has an error rate of 1.9%. But the error rate is now likely even lower, now that GPT-4 can live search the internet (albeit, it’s pretty slow). Turns out that AI was “hallucinating” papers that did not exist—but that it reasoned should exist based on its synthesis of the facts it has access to. Cool. Weird, but cool. I won’t miss it, but it was an interesting experience (and still happens some, I suppose).

Comparing physician and chatbot responses to patient questions on social media.

Patients preferred chatbot responses to physician responses 79% of the time. Some of this is likely because the chatbot gave longer responses—it doesn’t “cost” the bot anything to add in a few clichés and supportive words (“I’m so sorry to hear you aren’t feeling well! I hope you feel better soon”), whereas physicians have to take time to write those sentiments. We may be thinking them, but we don’t always have time to type them out. And patients like to hear that stuff. I don’t blame them. It works, even when I know it is pro forma.

Speaking of which, patients like to ask medical questions via text well later than business hours, research shows. Chatbots don’t get tired after dinner, and are always on call. While we’re at it, other research shows that doctors can’t always tell which responses were written by human physicians rather than chatbots. Convinced yet?

Chatbots are pretty good at clinical reasoning.

GPT-4 outperformed first and second-year medical students on clinical reasoning questions. So, this Thanksgiving, don’t ask your cousin who is a medical student about your back pain. Ask a chatbot. (Or a doctor). And when the chatbots were given highly challenging cases, the correct diagnosis was on the “list of possibilities” 64% of the time (and was the lead suspect 39% of time). In another study, when the bots were given very tough cases (that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine), the right diagnosis was made 58%-68% of the time. Granted, I’m not an internal medicine physician, so this is not my area of expertise, but I don’t think I’d do nearly that well.

AI can read your chest x-ray.

Kind of. The model did well in picking up a very obvious dangerous condition in one study (a collapsed lung). But I’ve been testing ChatGPT’s ability to read more routine chest x-rays lately (GPT-4 now lets you upload pictures), and, basically, so far it is not great. Apparently AI modules built for just this purpose are very good. But currently, my iPhone and GPT-4 aren’t cutting it. (I also tried showing it some ECGs; it missed an important diagnosis. When I pointed it out, it cheerfully admitted that it had missed it and thanked me for pointing it out. Very polite. See above under: I know it is a bot but manners kinda do make a difference!)

There’s much more to come on this.

The future…

How do I think this will affect patient care? Well, for one thing I think it will revolutionize everything (including medical education). I predict GPT will be similar to what we experienced 20 years ago with Google—but on steroids. Laypeople Google stuff about medicine. Doctors Google stuff about medicine! The key is how we interpret information we are given, whether it’s a Google search or an AI “conversation”. I’m not worried about my job security. But I am sure that I’ll look back on my life as a physician in the pre-AI era and wonder how we ever survived.

*I use GPT to copyedit Inside Medicine. It suggested that I change “But it also lied to me” to “But it also misled me” (italics added). Sometimes I do wonder if there’s sentience in there!

Thank you for the Case Report Doctor but, my ER Doc ... fyi, she is faster than AI.

Nice, thank you.